The Impossible Challenge

Inaugural competition aims to solve the world’s biggest problems.

By Morgan McFall-Johnsen

On a Monday evening in mid-February, while hundreds of students filled the library cramming for Chemistry tests and churning out history papers, 46 students divided into nine teams prepared for a presentation they hoped would help change – maybe even save – the world.

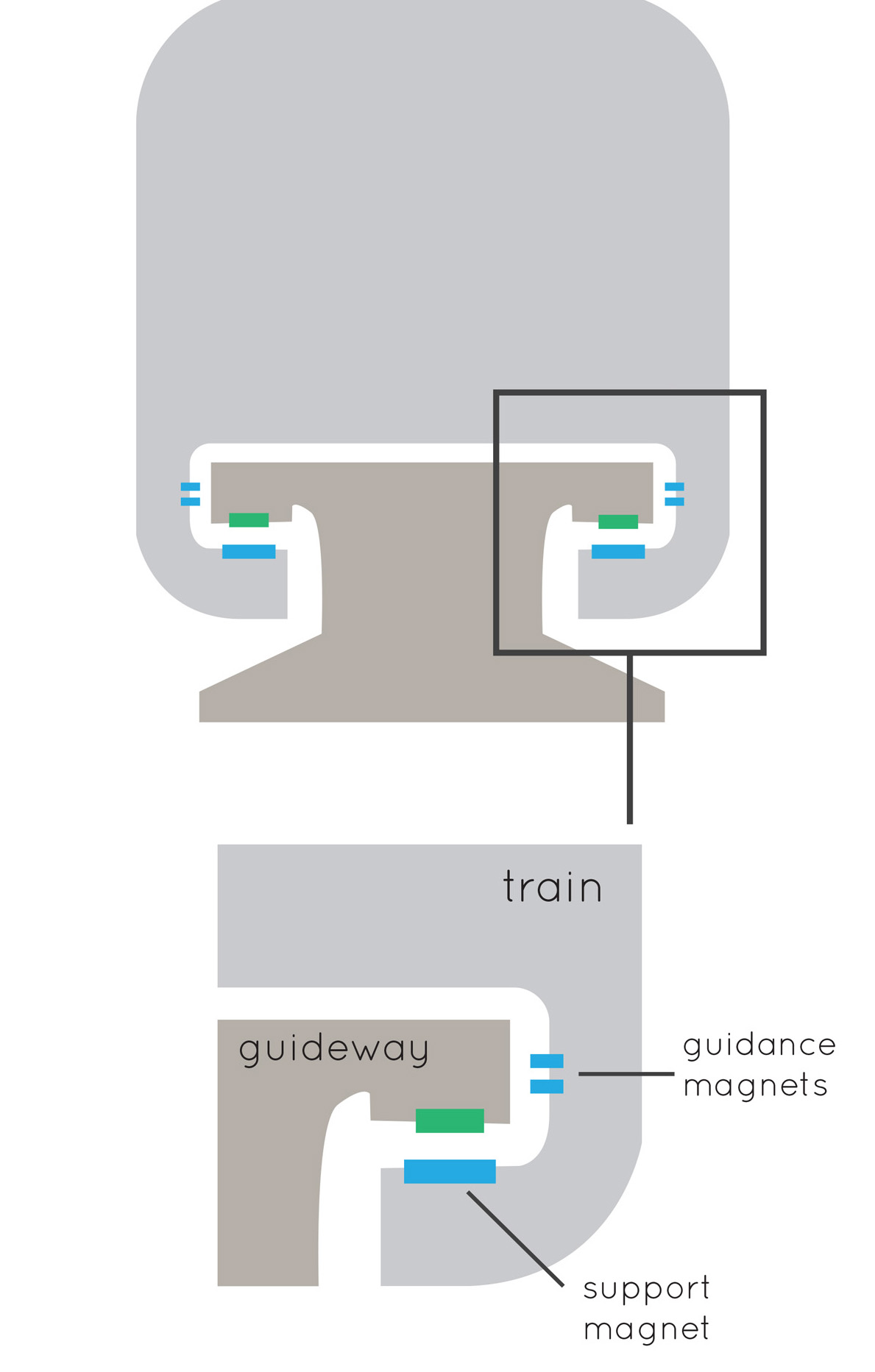

Two teams analyzed state-of-the-art agriculture technology to grow crops without soil in crowded cities and disaster zones. Another two explored oil-free magnetic levitation driverless cars and trains that could travel upwards of 186 miles per hour. One team analyzed solar farms and another built-in solar panel roofing. But regardless of project or topic, every team has one goal: to find the best solutions to climate change.

Formed this school year, the Impossible Challenge draws inspiration from a step-by-step process for solving global issues laid out in retired computer programmer and systems analyst David Paul’s book, Standards that Measure Solutions: A Guide to Solving 21st Century Problems. Each year, the program will address a new major global issue for which solutions are complex and difficult to implement – what Jeffrey Strauss, the program director, calls “wicked problems.”

The Impossible Challenge is just the first step or the “first-cut analysis” phase in Paul’s book. Students do not try to enact the plans, but instead analyze how likely they are to be implemented and how effective they would be by looking at economic, political, social and technological feasibility.

“I’ve seen a lot of the programming with student groups at Northwestern and Impossible Challenge was very different from anything I’ve seen,” says Victoria Yang, a Weinberg senior on one of the two teams analyzing different sustainable transportation systems. “The project is very open and it allows students to be creative.”

Students do most of their research independently, while meeting with their group throughout the quarter. After final presentations on May 26, each student will receive a $500 stipend, and the winning team will receive a $5,000 cash prize.

But the students have their own reasons for joining the project. For many, it’s a chance to explore fields, like transportation technology, that are not part of their academic experience.

“This was a taste of something that I couldn’t have done otherwise,” Yang says. “It intrigued me so I wanted to be involved and this allowed me to do that without having a physics background.”

Weinberg junior Kathryn Kim is on a team working on aeroponics: using mineral-filled mist to grow food instead of soil. Kim, a pre-med student, analyzed the political feasibility of her team’s project, allowing her to use her political knowledge outside of conversations with friends for the first time.

“I was interested in [the Impossible Challenge] because it was a year-long project, so it required a lot of time and devotion,” Kim says. “I like that commitment to it because it made it seem like it would be something worth doing.”

But with every solution comes complications. At their midterm presentations, for example, Yang’s team presented the benefits their magnetic levitation train system could have in India: perfect fuel efficiency, noiselessness and speed. But the judges pointed out the trains would not accommodate India’s growing population and corruption would deter investors. Aeroponics systems could make food deserts sprout fresh produce, Kim’s team says, but would require high amounts of energy and could force farmers out of jobs.

For the students, though, the program makes a difference, regardless of whether the solutions come to fruition, through education and raising awareness around climate change.

“It will make people take a pause and think about [climate change] more thoroughly and I think that’s, in and of itself, a way to say that this is working,” says Weinberg sophomore Caili Chen, a member of the aeroponics team.

Next year, the Impossible Challenge will start up again with a new crop of students and a new global challenge.