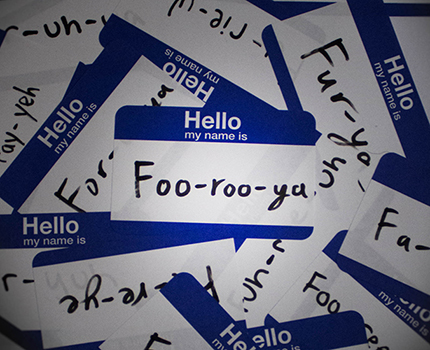

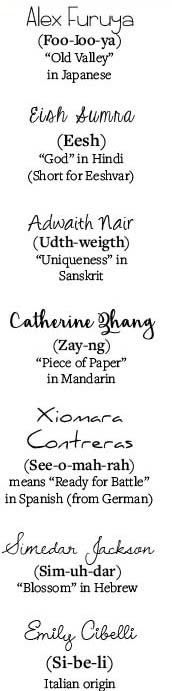

Furuya. Not with a soft “R” like ribbon, but with a rolled “R” almost like an “L.” There’s no trick in the vowels; it’s pronounced just how it looks and almost rhymes with “Tutu, yeah.” As simple as it is to me, my last name has always been challenging for people to pronounce. I’ve gotten surprising variations of my name – Fur-rai-ya, Fer-ya, even Ferrari. More often than not, when people read my name aloud, they won’t even attempt to pronounce my last name and simply say, “Alex–” as if they were interrupted. Often I just nod, but if they ask, I tell them it is “Foo-ɺoo-ya” (ɺ is a unique Japanese sound pronounced similarly to a rolled "R"). It does not carry a fancy meaning – in fact, the literal Japanese meaning is “old valley.” However, I still feel familial, cultural and personal ties to it. It is my identity, and too often it is butchered.

Students like me wince when our names are mispronounced. It happens often, but every time I feel a certain twinge. Some, like Adwaith Nair, a McCormick junior, have lived with an alternate version of their names for more than half their lives.

It was the first day of kindergarten. Adwaith, then a shy kid, was as nervous as any kid on their first day of school. The students introduced themselves, and everything went smoothly until it was Adwaith’s turn. He told the class his name – “Udth-weigth” – but his white, middle-aged teacher couldn’t get it. He tried again, but she still didn’t get it. Finally, after repeating his name for the third time, he gave up. The name stuck – “Ad-with.”

Adwaith, whose name means “uniqueness” in Sanskrit, attended the same predominantly white school system from kindergarten to high school. “For like 12 years people would just mispronounce my name,” he says. “It wasn't really a thing you could change halfway through.”

Names come from a lot of places, both geographically and historically, and often hold personal significance for an individual. In the U.S., and especially at Northwestern, non-Western names, both first and last, are common. According to numbers published by the International Office, the number of international undergraduate students increased about 60 percent from the 2010-2011 school year to the 2016-2017 school year, from 508 students to 815. This number doesn’t even include students like me who were born in the U.S. but have non-European names.

My last name, “Furuya,” is a common surname in Japan. Still, it gives me power. It ties me to my paternal grandfather, who become a dentist to avoid the draft in Japan. It ties me to my paternal grandmother, who couldn’t be a doctor because of restrictive gender norms. It ties me to my parents, who left their stable home to move to the U.S. in hopes of giving their child more opportunities. In the process, they sacrificed a lot. My family inspires strength, and so does my last name.

When I was in high school, I used to pronounce my name in a more American way to avoid the five-minute awkward conversation about the correct way to pronounce my last name, where it comes from and what it means. So I have two last names, Fur-roo-yah and Foo-ɺoo-ya. It’s a common strategy for many.

“I know that there's a specific way to say my last name and to be honest, most of the time when I tell people my last name, I say it in the Americanized way,” says Catherine Zhang (Zay-ng), a Medill junior. “Just to make things easier because it's easier to pronounce.” Students sometimes shorten or alter their names in everyday conversation to make them easier to read and pronounce.

“When I was younger, people would always have trouble with my name, especially from teachers, like during roll call,” says Simedar (Sim-uh-dar) Jackson, a recent Medill graduate who now lives in New York. “When they would get to me there would always be a hesitancy and then they would just say, ‘Jackson.’ It became such a thing that I went by Simmie.”

Simedar had another reason to change her name: she also didn’t want the negative stereotype that follows Black women with “different” names. When she was just in elementary school, an adult told her that her name was “ghetto.”

“I really internalized that and that made me feel like my name wasn't worthy,” Simedar says. “I didn't want someone to automatically think that I was, quote, ghetto, and discredit everything else that I would say after.”

Most people don’t mispronounce names out of malice. They do so because certain names come from different languages and have little in common with English names, according to Emily Cibelli, Ph.D. (Sih-be-li), a research associate and lecturer in the Department of Linguistics.

“There's two hurdles you have to overcome,” Cibelli says. “First is that you have to recognize that the sounds are different from the ones in your own language.”

The second part is actually being able to pronounce the name. “You've got this listening challenge and you've also got this pronunciation challenge,” Cibelli says. “Those together, unless someone sits you down and actually instructs you on the pronunciation, is where people often stumble in pronouncing something from another language or another culture.”

English, in particular, makes it harder for people to correctly pronounce non-Western names. According to Cibelli, the spelling of a name and the pronunciation of a name do not strictly correlate. “My last name, for example, is Si-be-li, a lot of people look at it and pronounce it as ‘Chibelli’ because they know of other Italian American names pronounced that way. ”

When I was a kid, I was teased for having an accent, so I would stay in my room practicing my vowels because I wanted to fit in. I hated my last name because it contained remnants of a language that others didn’t value, one which made me automatically different. If I said my last name the Japanese way, I was afraid I would revert to my “foreign” accent.

Every time someone mispronounces my last name, I am reminded of those long hours spent trying to pronounce words like “development” and “volcano” and wishing I wasn’t Japanese.

The anxiety you feel right before someone new mispronounces your name isn’t just a childhood struggle. In fact, it can happen here on campus, and to a greater degree. Eish (Eesh) Sumra, a Medill junior, remembers this anxiety during Wildcat Welcome, even after three years. As part of an orientation game, his PA group had to go around in a circle and say their names, along with the names that were introduced earlier.

“Someone said, ‘Meish,’ and someone said ‘Seish,’ and someone said ‘Shaish,’” Eish says. “I've said it so many times but people couldn't just get it. I couldn't understand why. Even the PAs didn't stop it 'cause I don't know if even they knew what my name was.”

Sometimes, however, mispronunciation can help a group of students come together. When I’m with my Japanese friends and family members who live in the U.S., we laugh when people try to say our names out loud. For us, the pronunciation of our names is as obvious as knowing the alphabet. And yet most people have trouble pronouncing common Japanese names like Noriko and Aiko.

According to Simedar, having a name that is often mispronounced is one small component of the minority identity, but also one that can bring people together.

Simedar says. “I think for that very fact, a lot of my friends had first or last names that were not typical and we all had some connection to wanting someone to pronounce our names correctly.”

While the process may be awkward, there are certain ways to go about learning people's names. The biggest mistake you can make when you encounter a name you are not familiar with is to not try – or worse, offer nicknames.

“When I introduce myself and you don't ask or don't try, that's when it bothers me,” Communication senior Xiomara (See-o-mah-rah) Contreras says. “If it's just you being lazy, I don't understand why I have to [make the effort].”

Rather, the first step is to ask. “I don't like when people try, like they're like, ‘Ehhh.. ish?’ Don't do that cause that's just stupid. Just ask,” Eish says.

The second step is persistence. Recognize that name pronunciation is difficult but important. I do not mind if you ask me how to pronounce my name multiple times – in fact, it makes me happy because it shows you care. Don’t take it personally when we correct your pronunciation.

“People have to eventually learn it, and so you may as well force them by just keep going on,” Eish says.

Finally, just keep practicing pronouncing the name. Every name is pronounceable. Breaking a name into bite-sized pieces is a great tactic.

“I honestly keep repeating [my name] until they say it correctly,” Simedar says. “Every time they say it wrong, I'll be like, ‘Sim-uh-dar.’ When you break it down into a couple of syllables, it usually only takes a couple of tries.”

Furuya. I used to hate the rolled “R” that sounded almost like an “L.” I hated how people thought there was some trick in the vowels. My name was so obvious to me that when I heard people mispronounce it, I thought they did it on purpose. It took some time, but now I appreciate my last name. When I see my last name, I think about my grandparents, my relatives and my parents and all the sacrifices they made so I could be here today. I don’t think about the time I spent trying to perfect the American pronunciation of my name. Although I still wince when people butcher it, I now love my last name. It’s pronounced “Foo-ɺoo-ya.”