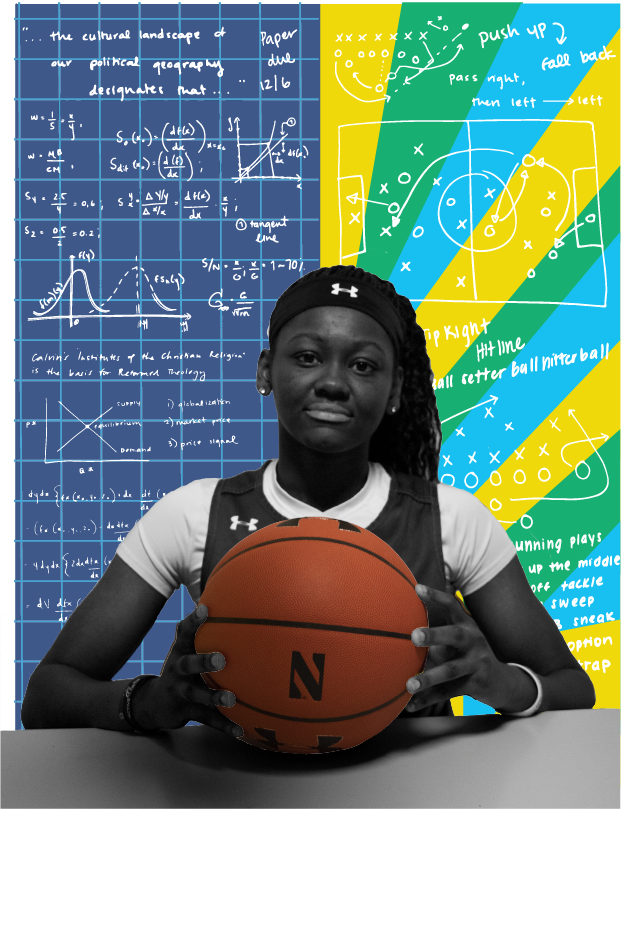

Tackling the hyphen

Student–athletes struggle to balance top-tier expectations in the classroom and Big Ten pressures in competition.

By Anabel Mendoza

Lindsay Adamski, a pre-med senior and co-captain of Northwestern’s women’s swim team, approaches the pool’s starting block for the women’s 200 medley relay. The odor of chlorine stings the air as fans dressed in purple t-shirts and baseball caps crowd shoulder-to-shoulder on the bleachers of the Norris Aquatic Center. The spring of the diving board heard pulsing in the background begins to fade among the crowd’s whistles and cheers. The pool is Adamski’s home.

Adamski, who wears a black swimsuit embellished with a purple “N,” a black, latex swim cap and mirrored swim goggles, is nearly unidentifiable among the crowd of other Northwestern swimmers. She walks past the scoreboard, past the bleachers designated for the different teams and past the divers thrusting themselves into the air before landing in the water without a splash, to arrive at the starting block. She places her feet firmly, left foot forward, into a lunged, take-off position. Her eyes focus intently on the water, while her arms begin to sway slightly back-and-forth in anticipation. She is ready, zeroed in only on herself and the lane in front of her. In just a few seconds her race will begin, and she’ll plunge herself into the pool. For that moment, it’s just her and the water. The stress of her upcoming midterms, the research she commutes to and from downtown Chicago to conduct and her meetings with coaches and doctors, among a number of other commitments, cease to exist for the 30 seconds she is racing.

The race marks the beginning of an onerous weekend for Adamski – competition from 5-9 p.m., practice the next morning at 6 a.m., midterms due Sunday evening and studying for the MCAT in March. The constant demands of Northwestern’s Division I athletics and top-tier academics are an all too familiar reality among the lives of student-athletes. As Adamski says, “We know we’re going to have to get up early; we know it’s going to hurt.”

This pain isn’t always physical. Rarely is there a time when a student-athlete can just be a student or just an athlete. They are living in a hyphenated world. Physically and theoretically, academics and athletics are kept separate. Student-athletes find themselves constantly balancing expectations from these disparate sides, living at the intersection of physical perfection and academic success, stretching themselves to meet expectations from coaches, trainers, professors and classmates, expectations that don’t find space to coincide.

/

Whether you’re a Northwestern student-athlete or a “narp” – a “non-athletic regular person” as collegiate athletes commonly refer to their peers – you’ve likely heard the number: $270 million. The newly constructed Walter Athletic Facility stands lakeside, its modern glass edifice and cutting-edge athletic technology representing the newest additions to Northwestern’s campus. But amid campuswide budget cuts and the exclusivity of the facility, which remains accessible only to student-athletes and their coaches, the building has been the cause of much frustration and tension among student-athletes and non-student-athletes. One student on the NU Crushes and Confessions Facebook page went so far as to call it the “temple to the football gods” and criticized the career, tutoring and nutrition services given to athletes, despite other students lacking the same access to these resources.

Looking in from the outside, it’s easy to mistake the new building for a luxurious resort, where student-athletes enter into a new dimension; a world of regular massages and therapeutic hot tubs, a fuel station conveniently stocked with an assortment of free snacks, laundry chutes where their dirty athletic gear vanishes into the abyss only to magically return freshly washed and dried. But the athletic facility also serves as a physical reminder that Northwestern student-athletes and non-student-athletes co-exist on one campus, but in two separate worlds.

Daily grind

At the Big Ten Swimming and Diving Championship back in February, swimmers from Big Ten schools across the country were beginning to warm up in the pool. Out in the hallway, Adamski sat with her laptop, typing away to complete a paper with an alarm clock ticking down to race time. Despite having an hour and a half to warm up, Adamski spent 45-minutes in the pool, in order to leave time to finish an assignment due later that night. When she eventually finished, Adamski quickly shut her computer, running back into the pool to grab her suit, change and compete. During the championship, Northwestern’s men’s and women’s swim teams often travel for an entire week to compete. For Northwestern swimmers and divers, the championship usually takes place in the middle of winter quarter, during a time when other students on campus are preparing for their first round of midterms.

The feeling of a pressing deadline causes much stress for students as it is. They can often ask professors for extensions, or, in the case of student-athletes, try to meet with one of the 70 individual tutors Northwestern athletics has dedicated to an exclusive tutoring program. Adamski often holds herself back from asking for that help, though. “I have the type of personality that I don’t want to do that,” she says. “I don’t want me being a student-athlete to be [the reason] I get special benefits, special perks because of what I’m doing. I’ve never asked for an extension because I’m like the deadline is here, I need to figure it out and get it done.”

Regardless of how much Adamski might benefit from an extension, asking for help comes from an underlying worry that non-student-athletes will see her, a student-athlete, as someone receiving special treatment. So instead, she chooses to hold her tongue.

According to a survey by the American College Health Association, student-athletes nationwide report “four nights of insufficient sleep per week,” given how much of their time is consumed by travelling, practice and balancing schoolwork. The NCAA reported that one-third of student-athletes are consistently sleeping less than seven hours a night, which often leads to difficulty concentrating and performing both athletically and academically throughout the day. Healing and recovery from physical injuries and conditioning happens during these essential hours at night, so limited sleep leads to even more physical strain on student-athletes’ bodies.

The physical exhaustion, though not unusual for student-athletes – especially those like Adamski who must follow an evening of competition with an early-morning practice – becomes intensified during the week when classes and meetings are added to their meticulously planned schedule. The most prevalent case is when the fatigue of their early-morning workouts catch up to them in the classroom. For Adamski, that has often meant teaching herself the course material after class. “A lot of times I find myself zoning out no matter how much coffee I have,” she says. “It’s so hard to focus.”

But in many ways, that constant mental and physical fatigue has become second nature. Across campus, alarms begin to ring at different intervals of the morning; athletes like Jones begin to wake to meet their coaches and teammates often well before the rest of the student body starts their days. “We practice Monday through Thursday, but Tuesdays are our really tough days where we condition. Wednesdays are still really hard physically,” he says. “Not to mention we still lift two times a week on top of that … By the time I go to class, I’ve already been up for like six hours.” For Jones, starting his days at the break of dawn is his college experience.

From basketball to swimming to football to lacrosse, the daily schedules of student-athletes differ team-to-team but remain largely structured by the same fundamental building blocks: practice, games or competitions, conditioning, team meetings and mandatory study hours. Everything is planned to a tee. According to NCAA regulations, student-athletes can train a maximum of 20 hours per week in season and eight hours per week during offseason; coaches rarely end weekly practices before this cap.

A recent study which surveyed over 44,000 Division I student-athletes, in addition to over 2,000 administrators and 3,000 head coaches, concludes that most student-athletes would like a mandatory 2-week “no-activity” period after their season is complete, while coaches in men’s football and men’s and women’s swimming primarily do not support as much time off. Similarly, during the post-season, student-athletes responded that they’d prefer fewer than eight hours per week of training, while coaches preferred more hours per week. However, these often contested measures rarely account for the additional time spent traveling or attending team meetings.

“Generally during the week, I would say, probably three to four hours in total watching film, going over the plays, knowing what you need to do,” Jones says. “Not to mention your four classes that you’re taking.” On top of this, Northwestern football players lift two to three times a week for about an hour each session. This combination of physical and mental work required of student-athletes often makes it difficult for them to find time in their days to unwind and relax. While coaches and trainers might encourage student-athletes to prioritize mental health, as was the case on the women’s basketball team, often the University’s high-expectations for student-athletes to perform athletically and academically, in addition to their overloaded schedules, makes prioritizing self-care impractical.

Even on their once-a-week off-days, student-athletes still feel an underlying expectation to work on perfecting their athletic craft. Student-athletes not in the gym during their day off are often found in the library or locked in their rooms catching up on schoolwork to make the deadline for an assignment.

While student-athletes have certainly chosen a college-experience heavily devoted to playing Division I sports, their time spent in the weight room or travelling every other weekend to compete naturally limits the time they can devote to doing assignments, studying both in and outside the classroom or taking on part-time jobs during the school year.

Nonetheless, some student-athletes often feel a lone responsibility to manage their athletic and academic careers out of fear that non-athlete students will criticize them for receiving special benefits. But many argue being a student-athlete never ends: they are constantly faced with the expectations of both jobs.

An imposter on campus

The smell of antiseptic lingers in the air. Lab benches line the room, equipped with two spots on each side for lab partners to work together. Bench-after-bench, lab partners armed with white coats and safety goggles begin gathering beakers and pipettes for their assignment. Among the crowd of pre-med students is Adamski, who asks around for a partner when it seems everyone but her has found one. “Does anyone want to partner up?” she asks. Chatter between already-established pairs picks up, as groups begin working, leaving Adamski completely on her own. “Everyone else would partner up,” she remarks, “I’d be the last person. I feel like I add value, but … I’ve learned to not identify myself as an athlete.”

Adamski isn’t alone in feeling this way either. Often, to be taken seriously within Northwestern’s rigorous classroom setting, and more importantly, to feel accepted on campus, student-athletes have felt they must conceal all parts of them that are tied to Big Ten athletics, to the newly constructed Ryan Fieldhouse and to the perks that some non-student-athletes are quick to criticize them for having.

“I try to wear regular clothes for the week because the non-athletes tend to not like athletes in the classes that I’m in,” Sandra Freeman, a junior pre-med student says. “I first like to establish myself as someone who is equal to everyone else in knowledge and ability and commitment before I tell people that I’m an athlete.”

It’s a common fear among Northwestern student-athletes that their athletic clothes stand out as obvious red flags among non-athlete students. Their personalized backpacks and embroidered attire call attention to their lives as athletes, and like the new facility, they believe a similar narrative is passed forward: this time, a narrative that student-athletes are somehow less capable when it comes to academics which they feel many have internalized throughout their time at Northwestern.

Standing at 6-foot-2-inches and short-spoken, School of Communication senior and starter on the women’s basketball team, Pallas Kunaiyi-Akpanah, began playing competitive basketball at 14-years-old, shortly following her move to the United States from Nigeria. Her hope, she says, is to be drafted to the WNBA after she graduates early following winter quarter. While the prospect of playing professionally isn’t always a reality for student-athletes after college, NU for Life, a professional development program for student-athletes on campus, helps to equip many with the resources necessary to excel professionally upon completion of their athletic careers. But similar to Freeman, Kunaiyi-Akpanah felt her athletic gear would out her to “narps” on campus. She says she was afraid of suddenly becoming synonymous with unintelligent, indifferent and completely antithetic to the hard-working, driven population of true Northwestern students – those who have been accepted based on academic standing and achievement.

“When I first came as a freshman, [and] sophomore, I was a little concerned about how I would be perceived coming to class with sweatpants and a hoodie on,” says Kunaiyi-Akpanah, gently clasping her hands together, pausing briefly while her eyes drift to look at the ceiling. “I was afraid of how people might see me as a first impression, like ‘maybe she’s not smart or she doesn’t take school seriously’ or something like that.”

Yet, even when it comes to student-run social events and extracurriculars beyond the classroom setting, the day-to-day schedules of student-athletes, complete with a variety of athletic obligations, make it nearly impossible for them to attend on-campus events hosted by their non-athlete peers. Whether it be Refusionshaka performances, student-run comedy shows or affinity group meetings, often the activities and extracurriculars that are central to an undergraduate’s experience are not always feasible for student-athletes to become involved in. Though it can be difficult, sometimes they can find moments to share in these larger communities on campus: Pallas made time to perform a comedic act for the Afropollo talent show, winning third place.

“My schedule doesn’t allow me much socializing with students in general. We’re always with the athletes, we’re always traveling … That could be a reason why they feel like they don’t really accept us, because they don’t get to see us a lot,” Kunaiyi-Akpanah says.

Like Kunaiyi-Akpanah, some student-athletes have come to see their occupation of this remote space at Northwestern as being a byproduct of their physical absence from campus, further restricting the opportunity to develop relationships with non-student-athletes.

Mapping out race

Inside the 555 Clark lecture hall of African American Studies 212, dozens of students begin to trickle in minutes before class starts at 9:30 a.m. Among the group is a large number of student-athletes. Lauryn Satterwhite, a sophomore basketball player in Medill with an infectious smile and “In Jesus Name I play” bracelet, makes her way with the group toward the back right of the room. Many of them, having come straight from practice, carry to-go boxes filled with fresh fruit and breakfast burritos, attempting to eat while taking notes. All sitting together, Satterwhite and the rest of the student-athletes are a throng of athletic hoodies and Under Armour backpacks surrounded by non-athletic students.

It is clear that a separation exists in the classroom between student-athletes and non-student-athletes. However, for student-athletes whom the intersections of race already situate them as minorities on Northwestern’s predominantly white, wealthy campus, the struggle to belong is exacerbated.

“As a student-athlete, I already feel out of the loop with things like even with the Black culture on campus, I still feel like I’m out of the loop on it just because I am an athlete,” Satterwhite says about being a Black student-athlete at Northwestern.

Last year, Satterwhite received a text from a friend in one of her journalism classes who invited her to a Black student event on campus. “When I got there, first I was like ‘Wow, I didn’t know there was this many Black students on campus,’” Satterwhite says. “That was like my first impression, and then second, I was like ‘this is kind of cool, I wish I could get invited to more of these.’”

For Satterwhite, this was a moment in which being invited for the first time also made her realize just how many events she had missed. There were already communities and friendships among Black students on campus that began forming without her, so despite the invitation, Satterwhite couldn’t help but still feel uninformed.

“Then I found out that they had all these GroupMe’s, like the ‘Black @ NU ‘21’ group chat, all these group chats that me and Lindsey,” another Black basketball player, “weren’t in … they had all these events, yet they didn’t make an effort to reach out to student-athletes and become friends with them and invite them.”

This obscure middleground where Black student-athletes like Satterwhite struggle to feel a part of the larger community of Black students at Northwestern complicates this constant juggling between the two identities of “student” and “athlete.” Instead, for many student-athletes of color, finding where they belong is muddled as they try to navigate these overlapping, yet very different spaces as students of color or student-athletes of color. In moments when students like Satterwhite struggle to feel part of Northwestern’s community of Black students, it is the athlete label that continually seems to place them as outsiders.

Satterwhite’s sentiments are not a new feeling for Black student-athletes at Northwestern. In 2016, Johari Shuck, a professor at Indiana University, who studies racial diversity issues in higher education, visited campus to talk to a six-person panel made up of current and former Black student-athletes at NU. One panelist, Derrick Thompson, a football player from the class of 2000, noted how walking into the Black House as a first-year student, he was perceived as solely an athlete and not as a Black student. In his research Shuck states,

“[Black student-athletes] can’t always relate to the [non-athlete] Black student… Wedges exist because Black students don’t understand the experiences of Black athletes, and vice versa.”

While the challenges of feeling a part of Northwestern are often compounded for student-athletes of color, Satterwhite and other student-athletes of color’s experiences do not stand for the entire Black student-athlete or student-athlete of color community. As Shuck would say, this isn’t a “one shoe fits all” experience. “What being a Black person is to you might be different for what it is to me.” These experiences, too, are uniquely different in each space that Black student-athletes and student-athletes of color occupy too, whether that be spaces of color, the classroom or the gym.

Shortly after Northwestern’s football team won the Big Ten West title, many non-athlete students took to social media. Celebratory captions such as, “Cats are Best in the West,” “NORTH(BEST IN THE)WESTERN” or simply “SPORTS” with a link to a local news story about Northwestern winning the Big Ten West title for the first time, appeared everywhere. The win brought a wave of excitement across campus, as many students celebrated the victory, proud to claim Northwestern and the win as their own. But as a result of the win, the football season was extended by a week in preparation for the Big Ten Championship game in Indianapolis on December 1. Many football players from outside of the Chicago area did not go home for Thanksgiving and instead spent the holiday training with the rest of the team for the last regular season game against Illinois. That said, it’s difficult to find a single football player who complained about missing out on a brief break from classes and time spent with family and friends, because playing is what they love doing. When the alarm rings at 5:30 or 5:45 a.m., their bodies might ache for a few more hours of rest, but every day they will get up, they will train and they will attempt to manage life as student-athlete the best they can.