Imperfect But Imperative

Affirmative action is on the line again in the lawsuit against Harvard. But this time, access to higher education, even at Northwestern, may actually be in danger.

By Mila Jasper

When Weinberg junior Emily Guo wrote her college essay, she looked to her sister and one of her closest friends to help make the story personal. She wanted to write about her identity, but needed help working through exactly what that entailed.

“It wasn’t easy for me to write,” Guo says. “I didn’t really know how to express it because not only was I trying to understand it for myself, but [also to] put it in a way that other people could empathize with.”

Guo is Chinese American. On paper, she says her upbringing fits common stereotypes often assigned to Asian Americans: she was studious, quiet and played piano. But she was also active and involved in sports. For a long time, she felt that it was hard to embrace her Chinese heritage. Her small, upper-middle class community on Boston’s North Shore was predominantly white, and in some ways, she felt as though she was “passing for white.”

“I was like [Asian American] is a category that has been assigned to me, but this is all of the complexity that I’ve had to deal with in it,” Guo says, “And also all of the ways that it just doesn’t fit with what I am.”

She wanted her personal statement to write the narrative of who she was before college admissions officials could write one for her.

/

This problem isn’t exclusive to Guo; all college applicants have to figure out how to use their essays to make themselves more than a list of test scores and extracurriculars. But according to Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA), a group of rejected applicants suing Harvard University, Asian American students carry an extra burden to prove themselves in the admissions process.

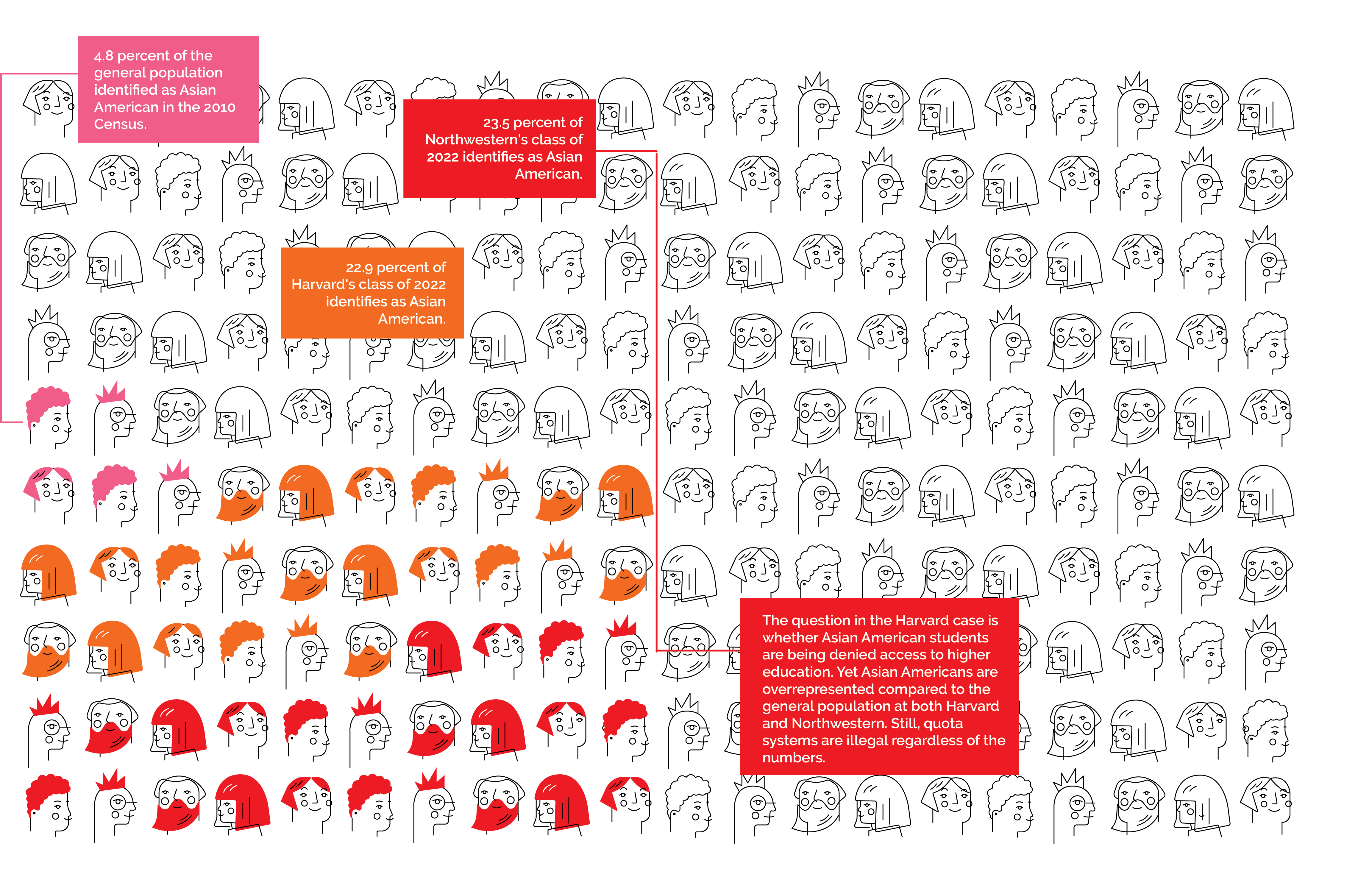

SFFA is accusing Harvard of engaging in racially biased admissions practices by creating caps on the number of Asian American students admitted. The group claims that Asian Americans were consistently scored lower on the “personal ratings” category — where applicants are rated on factors such as “kindness,” “courage” and “likability”— of the application, despite strong results on test scores and in extracurricular activities.

The argument in this case isn’t new. The same man who organized SFFA, Edward Blum, was the force behind a similar lawsuit that made it to the Supreme Court in 2013 and 2016, where affirmative action was upheld. The argument has played out on Northwestern’s campus before, too.

How Northwestern fits in

In May of 1991, the Northwestern Review, a conservative and now defunct student-run weekly, published a story called “Separate and Unequal: An Investigation of NU Admissions reveals something less than equal opportunity.” Replete with a slew of non-committal quotes from then-Associate Provost for University Enrollment Rebecca Dixon and an “unavailable for comment” from then-University president Arnold Weber, the Review’s article exposed a potential issue with the way race in admissions is discussed. Their actual assertions went much further, claiming that the University was giving an “unfair advantage” to Black applicants.

The story was based on admissions data provided by anonymous administration officials, and said that the favoring of Blacks in admissions was hurting white students and minorities, specifically Asian American and Hispanic applicants. “This fact may be an ominous one for Asians,” the article reads. “As more Black students are recruited, more qualified Asians are likely to be rejected.”

And, in regards to low admission rates for Hispanic applicants, “some minorities apparently add more value than others.”

The Harvard case is more than just similar to the argument the Review made in 1991 – it has the potential to fundamentally alter college admissions across the country. It already has the backing of the Department of Justice, which in July submitted a statement of interest supporting SFFA, and according to The <i>New York Times<i/>, has reallocated resources from its civil rights division to investigations into university admissions practices.

The DOJ says that because Harvard receives funding from the federal government, it is subject to Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, and national origin in programs and activities receiving federal financial assistance. Northwestern, like Harvard, also relies on federal funding and is subject to Title VI.

“What the plaintiffs are hoping for in this case is that the court will overrule [Regents of the University of California v. Bakke’s] holding that you can have affirmative action in favor of African Americans,” Northwestern Professor of Law and Political Science Andrew Koppelman says. “The plaintiffs are hoping that the Supreme Court today, which has completely different membership than at the time of Bakke, will reinterpret the statute to say that universities cannot take race into account at all.”

This would challenge Northwestern’s “holistic admissions” process, which former University spokesperson Al Cubbage told The Daily Northwestern “looks at a number of different factors, including race.”

Koppelman says that should the Court move to overturn affirmative action, he expects universities to make their opinions heard so that they can continue to use race in admissions.

Over the summer, 16 universities did just that by filing an amicus brief in defense of Harvard’s admissions practices. Northwestern and the University of Chicago were the only U.S. News top-ten schools not on the list. That said, Northwestern has emphasized its commitment to holistic admissions that include taking race into account.

“Many other universities could have participated in the amicus brief,” University Spokesperson Bob Rowley wrote in an email to NBN. “Nothing should be read into the fact that Northwestern is not one of the amici, one way or the other.”

Tyler Washington, the VP of Accessibility and Inclusion for ASG, also expressed “entire faith” in University President Morton Schapiro and VP for Student Affairs Patricia Telles-Irvin to maintain their diversity practices, citing their “strong voices.”

“Northwestern is kind of in a tough place in that they are taking a lot of affirmative action steps,” Washington says, emphasizing the University’s 20 percent Pell Grant-eligible goal as evidence of its commitment to diversity. “I think they want to make sure Asian American applicants feel like they’ll be given a fair shake, so that’s probably the calculus that played into not making comments either way.”

Beyond the test scores

<i>The Review<i/>’s investigation began with a quote from Northwestern's admissions policy: “It is the policy of Northwestern University not to discriminate against any individual on the basis of race ... in matters of admissions.”

In the eyes of the <i>Review<i/>, the University was violating its own policy by admitting African Americans at a rate of 73 percent, compared to the 49 percent overall rate, even though the mean SAT score for African Americans was 1070 compared to the overall mean of 1240. These numbers were from 1984, the first year for which the Review had admissions data, but they followed similar patterns for each of the years they had statistics, 1984-87 and 1990.

Dixon said that the numbers cited in the Review’s article “didn’t sound right,” but later told the Chicago Tribune that the “thrust is not too far off.’’

“There is much more to a person than just a test,” Dixon told the Review. “Why do you keep going back to the scores?”

This question is the crux of the affirmative action debate.

“Race plays a pretty critical role in admissions if you are trying to build a diverse and complete and holistic class,” Washington says. “Some of those factors in having a holistic class aren’t captured in SAT scores and GPAs. That much is obvious to anyone who has just talked to another person before.”

In both the 1991 case at Northwestern and the current Harvard case, the argument has been that more qualified students are being locked out of elite schools to make room for Black students.

This line of thought pits minority groups against each other, yet regardless of which group is better off, all minority groups have been subject to the white majority, according to History Professor Ji-Yeon Yuh.

For example, Guo felt she had to defend herself for looking like an “overachiever” who only cared about school. According to Yuh, the very definition of “overachieving” in this context is derived from Asian Americans’ status being compared to white Americans. “If you feel like you’re doing something and you’re doing something well, [it’s] because you’re Asian and not just because you did the thing well,” Guo says of this stereotype.

Yuh agrees, citing the underlying meaning behind the label overachiever.

“[Overachieving] means that you’re not supposed to achieve that much,” Yuh says. “You’re ‘uppity.’ White people or white men were supposed to be achieving this, but instead you are, so you are ‘overachieving.’”

Pull quote: "Asian Americans and African Americans are not competing with each other for spots. They’re competing with white applicants for spots."

In the Harvard case, SFFA asserts that Asian Americans are subject to quotas to make room for other minority groups and white people. But Yuh says the position of all others has been crafted to prop up the white majority.

“The fundamental thing about college admissions is that Asian Americans and African Americans are not competing with each other for spots,” she says. “They’re competing with white applicants for spots, and nothing shows that more clearly than the case against Harvard.”

Yuh traces this conflict between minorities back to the civil rights movement in the 1960s, when she says the notion of the “model minority myth” first emerged. This myth is the stereotype still common in society today: that Asian Americans are high achieving and law- abiding citizens because of their Asian culture.

“Americans were saying through the model minority myth ‘look at these Asians, they are succeeding, that proves there’s no racism, that proves that these Black people over here complaining about racism are complaining about nothing,’” Yuh says. “This is the beginnings of the ways in which the broader American society is deliberately pitting Asian Americans against African Americans.”

According to Yuh, the character judgments admissions officers make in the “personal ratings” category could be impacted by this myth.

“There are stereotypes ... about Asian Americans being nerdy and therefore lacking for the elimination of affirmative action is shortsighted, social skills, about Asian Americans being greedy, because they’re overachievers and therefore lacking empathy and kindness, and about Asian Americans being robotic because all they do supposedly is ‘study study study,’” Yuh says. “So the ways in which Harvard evaluates its applicants seems to replicate some of these stereotypes.”

SFFA has to prove that Asian Americans have actually been hurt in Harvard’s admissions processes, though.

“If, in fact, Asian Americans can’t show at trial that they’ve been hurt,” Koppelman says, “Then they haven’t got any basis for appealing because the trial court looks to the reports as a matter of fact.”

Class & building an application

Like many Northwestern students, when Weinberg junior Seri Lee was in second grade, they was learning addition and subtraction. And they was frustrated.

“My parents couldn’t help me with that because the way they learned how to add and subtract was different from the way the American school system teaches you,” Lee says.

Lee’s parents are immigrants. They didn’t go to college, and they don’t speak English. As a first-generation, low-income student applying to college, Lee faced extra challenges. “I had to navigate by myself,” Lee says. “FAFSA and CSS, they ask you to basically pull up your parents tax information as if an 18- or 19-year- old is supposed to know how to navigate taxes and that kind of information.”

As Lee’s story shows, disadvantaged students often carry more responsibilities with less access to resources and activities that can help them look attractive on applications.

Pull quote: "It [affirmative action] benefits the most privileged Black applicants. That this becomes the most prominent battleground for racial equality is racial justice on the cheap."

Test scores are heavily influenced by a students’ ability to pay for test prep, as well as by the quality of the education they received more broadly. Extracurricular activities can give a boost to applicants whose grades or SAT scores aren’t up to snuff, but those also require access, time and money.

“One of the characteristics of affirmative actions is that it benefits the most privileged Black applicants,” Koppelman says. “That this becomes the most prominent battleground for racial equality is racial justice on the cheap.”

Instead, Koppelman argues, policies like the 20 percent Pell Grant eligible goal are the path forward to ensuring diversity because they make college more accessible for lower income students.

“Northwestern is such a rich school that we can admit on a needs-blind basis,” Koppelman says. “Ultimately, what you want to do is have such a range of education opportunities that it doesn’t matter if you got into Harvard or Northwestern.”

Pell Grants are not enough to fully pay for Northwestern’s tuition, but the University’s soaring endowment can make up the difference for needy students.

This is not to say race shouldn’t be a factor in admissions, though, according to Lee.

“A reality with no affirmative action is worse than one with affirmative action,” Lee says. “I think that in this case there needs to be analysis of both race and class. There are wealthy people of color obviously, and if you’re wealthy you’re just going to become more wealthy, but that’s not saying race isn’t important.”

Even though racism has manifested itself in economic disadvantages to minority groups, such that minority groups often have higher ratios of poverty than whites, the raw numbers show that there are actually more white people living below the poverty line than minorities. So fully switching to class- based, race-blind admissions would not effectively foster diversity.

“It really depends on what kind of diversity universities are going to commit themselves to,” Yuh says. “Are they going to commit themselves to a race-blind socioeconomic diversity? Or are they going to commit themselves to a kind of diversity that is going to account all manner of things?”

After acceptance

The editorial that accompanied the <i>Review’s<i/> investigation asked, “at what cost and to what real advantage” is the University “admitting more and perhaps less qualified Black students,” pointing to relatively low graduation rates for Black students.

This indictment of Black students for being unable to keep up as a justification for the elimination of affirmative action is shortsighted, according to Lee.

“I think, personally, diversity and inclusion is bullshit,” Lee says, noting that without support, disadvantaged students will struggle once they come to campus.

It has been widely reported across campus publications that mental health services at Northwestern do not adequately meet student need; this means low-income students and students of color like Lee feel like they have nowhere to turn when they experience this isolation.

“You need to change the culture and the practices of the University to actually really give these students from a diverse background equitable opportunities,” Yuh says. “People can’t succeed if they’re thrown into the water and told to swim. They succeed if they’ve already been taught to swim, and they’re familiar with the water, or if somebody can guide them.”

This frustration isn’t new, either. The <i>Review<i/> quoted Karla Spurlock-Evans, Northwestern’s former Director of African-American Student Affairs, expressing the same idea.

There is no doubt that lack of access to support services hurts all students, and particularly disadvantaged students, but how much responsibility universities should take on to make up for social inequality is an open question.

Northwestern can admit more Pell Grant students, but until access to high quality public education is available to all, and not just those who are privileged, the pool of qualified low-socioeconomic class students will naturally be smaller than it should be.

“The 1950s and the 1960s are seen as a time of amazing class mobility for Americans, and one of the big drivers of that is the G.I. Bill [which helped WWII veterans pay for college],” Yuh says. “So we might talk about, ‘Oh well, what can colleges actually do?’ Colleges can expand the middle class.”

While it was universities that educated these veterans, the access to higher education was made possible by the federal government, not the universities themselves.

Although the plaintiffs in the Harvard case argue that categorization is the essence of discrimination, simply eliminating the categories doesn’t alleviate the different levels of privilege to which each group has access.

The article in the Review took criticism from then-President Weber for ignoring 30 years of racial equality and progress on campus. In the 1960s, Northwestern’s campus was whitewashed. Affirmative action helped to change that, Weber told the Tribune. He went on to say that “affirmative action will eventually become self-effectuating” because minority populations would outnumber the white population in America. Twenty-seven years later, we still aren’t there.