Who's your caddie?

NBN follows Evans Scholars from the golf course to Northwestern's campus.

By Sylvia Goodman

After driving 45 minutes to the Westmoor Country Club in Brookfield, Wisconsin, Nathan Schimpf waited nervously on the podium. He stood before a crowd of about 60 Western Golf Association (WGA) directors, staff members, donors and supporters who read Schimpf's application aloud. After that, they launched into a series of questions on everything from his athletic career as a hockey player to his ability to overcome adversity. This lasted for 15 minutes. He was in the final stage of the application process to become an Evans Scholar.

“It felt like five seconds, and it’s extremely scary, but I got through it,” Schimpf says.

Schimpf and roughly 275 other students from around the country were picked to receive the Evans Scholarship during the 2017-18 school year. It includes free on-campus housing, a growing alumni network, social connections and, most notably, a full-ride scholarship to participating universities for four years. But the primary requirement is that all applicants for the Evans Scholarship must have worked for at least two years as a golf caddie.

That’s right – the people who carry the golf clubs for professional and amateur golfers alike. Apart from being excellent students with outstanding character and demonstrated financial need according to the FAFSA and CSS Profile, all Evans Scholars must have strong caddie records, meaning they caddied regularly and successfully without complaint from the golfers for whom they worked.

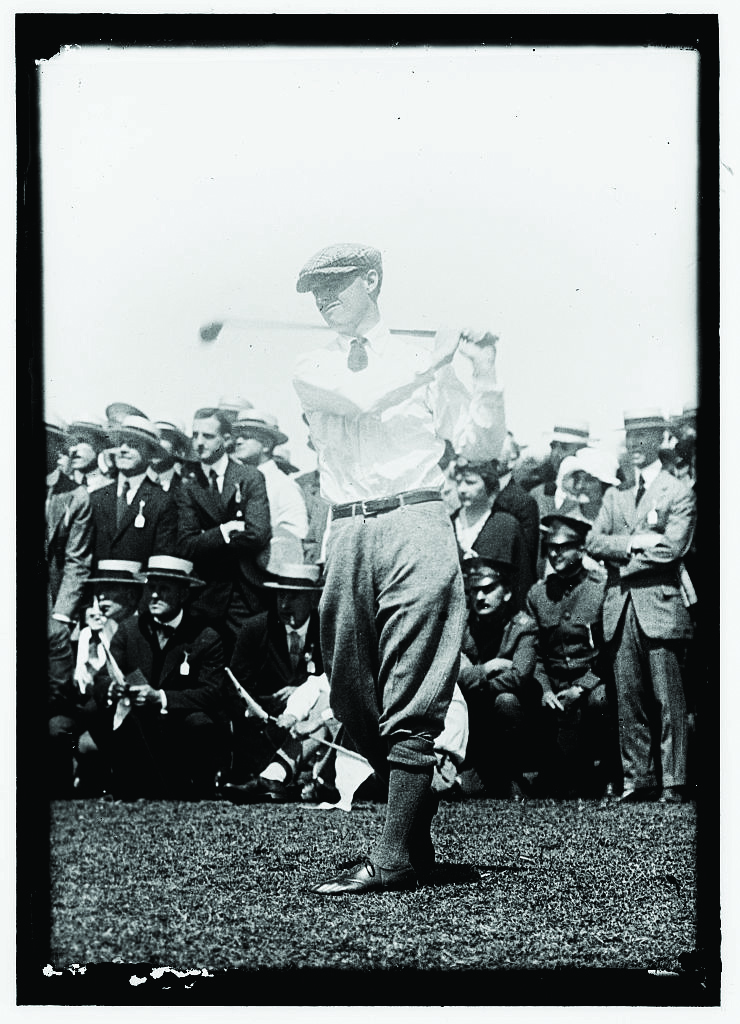

Though it seems oddly specific, the scholarship was started in 1928 by a caddie-turned-amateur golfer named Charles “Chick” Evans Jr. Evans himself had to drop out of Northwestern due to financial hardship during his first year, but he later became one of the greatest amateur golfers of his time, winning both the U.S. Open and the U.S. Amateur. To maintain his amateur status, Evans placed any winnings he garnered in a fund with the intent of awarding it to caddies with academic promise. Finally, in 1928 he convinced the WGA to oversee the fund, and the Evans Scholarship was born.

Caddie-turned-amateur golfer, former NU student Charles "Chick" Evans started the scholarship in 1928 after he won both the U.S. Open and the U.S. Amateur golf tournaments. / Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

In 1930, Harold Fink and Jim McGinni became the first two recipients of the award, graduating from Northwestern University in 1934. In fact, through the late 1930s, all Evans Scholars went to Northwestern until the WGA began parceling out scholarships to students going to other schools as well. Now, the scholarship extends to over 25 universities across the country.

So far, there are specifically-designated Evans Scholarship Houses at 16 universities. Northwestern’s Scholarship House was the first, established in 1940. Living in the Scholarship House for all four undergraduate years is a mandatory part of receiving the Evans Scholarship, which was originally cause for hesitation for School of Communication sophomore Mackenzie Lim.

“My mom wanted me to apply for it, but at first I actually didn’t want to apply for it. I was like, ‘I don’t want to live in a house full of caddies,’” Lim says, laughing. “But it’s definitely one of the best experiences. My Northwestern experience has been shaped totally by this.”

According to Schimpf, living together and seeing each other every day makes the Evans Scholars House a close-knit community. The faculty advisor for NU’s Evans Scholars, Martina Bode, attributed much of the Evans Scholar House atmosphere to the unique nature of the housing.

“I don't think you can find any other residence on the entire campus quite like it. It's really a family. It's a house where you have freshmen through seniors,” she says. “Staying in the house for four years really helps to build community.”

Northwestern’s Evans Scholar chapter also holds events throughout the year, many of which are golf-themed. Every year, they organize the Evans Scholars Open, their biggest philanthropic event, and raise money for different charities by setting up a mini golf course around the Scholarship House.

“A group of scholars put together each hole, and it’s really quite fun because it’s kind of a competition too,” Bode says. “Last year, one hole had little goldfish swimming around. I accidentally brought my doggies to the house. I wasn't looking, and they started drinking the water. It was just really fun.”

This year’s event was held on Nov. 11 and raised almost $2,000 for the Special Olympics of Illinois, according to Melina Scofield, the Northwestern Evans Scholar philanthropy co-chair. Scofield also says that this year’s event far exceeded their goal of $1,445, which was the amount raised from the 2017 ES Open.

This year, the Evans Scholars raised almost $2,000 at their annual philanthropy event, the ES Open. Proceeds went to the Special Olympics of Illinois. / Aine Dougherty

One drawback of the scholarship, however, is that it does not provide food to its recipients. Instead of having to fend for themselves, students have the option to get “meal jobs” on or near campus. In a meal job, a scholar helps out in the kitchens of a Greek association, local restaurant or sometimes even a school dining hall in exchange for meals. Sam Maciejewski, the Evans Scholars Foundation Manager of Education and Caddie Academies, says that while meal jobs are traditionally available for Evans Scholars, they are not mandatory and are not officially operated by the program.

At Northwestern, many scholars work in sororities because their house is located in the sorority quad.

According to Amy Fuller, the WGA and Evans Scholars Foundation Vice President of Communications, the scholarship is definitely in “growth mode.” The Board of Governors set a goal several years ago that will soon reach fruition: a thousand scholars by 2020. Currently, there are 985 scholars at 18 universities across the country.

“We’re certainly on track to meet that goal,” Fuller says. “Not only are we increasing scholars, but we’re increasing the number of scholarship houses that we’re opening across the country. We’re expanding our program from coast-to-coast.”

Fuller says that the committee that reviews applicants receives more and more applications every year. According to Fuller, the effort to expand the scholarship is made in order to keep up with the need for an affordable education.

While the number of applicants is going up, Schimpf says that many of the high school students he has spoken with are unaware that caddieing for a few years in high school could lead to a major scholarship.

“I tell people all the time, ‘I basically go to school for free because I caddied in high school.’ And they’re like, ‘Ah, I wish I would’ve known that,’” Schimpf says. “I wish they would have known it too.”

First-year college students can also apply for the Evans Scholarship, but it is much less common and remains primarily reserved for graduating high schoolers. However, college-level applicants must still have caddied in high school.

Ultimately, the goal of the Evans Scholar program is to grant academic and career-oriented opportunities. Schimpf, now a sophomore at Northwestern, says that he owes a lot to the Evans Scholarship.

“There is no way that I would be able to go here if I didn’t have this scholarship, because I just wouldn’t be able to afford it,” he says.

Recipients at Northwestern emphasize that the scholarship reaches far beyond the four years of college to future internships and careers, available through the extensive alumni network of over 10,000 men and women.

“Everybody looks out for each other, and if anybody’s looking for a job or an internship, usually somebody knows somebody else and things usually just fall into place,” Bode says. “So it’s usually not just four years of school. It’s a life-long friendship.”