Caring Through Comics

Feinberg's Artist-in-Residence is using comic books to help us think about illness and death in new ways.

By Daniel Fernandez

For five weeks this fall, eight medical school students gathered in a small classroom at Northwestern Memorial Hospital. They were there for a seminar called “Drawing Medicine.” It’s intended as an interlude, a break from memorizing the features of organ systems, the intricacies of gene expression, and the diagnostic protocols for all manner of maladies.

The instructor for the class, MK Czerwiec, has cropped blond hair, soft blue eyes, and a warm open face. She's a nurse, and a highly unusual one at that: For almost two decades she’s run a website under the pseudonym "The Comic Nurse”, where she illustrates the twists and turns that accompany health care in America.

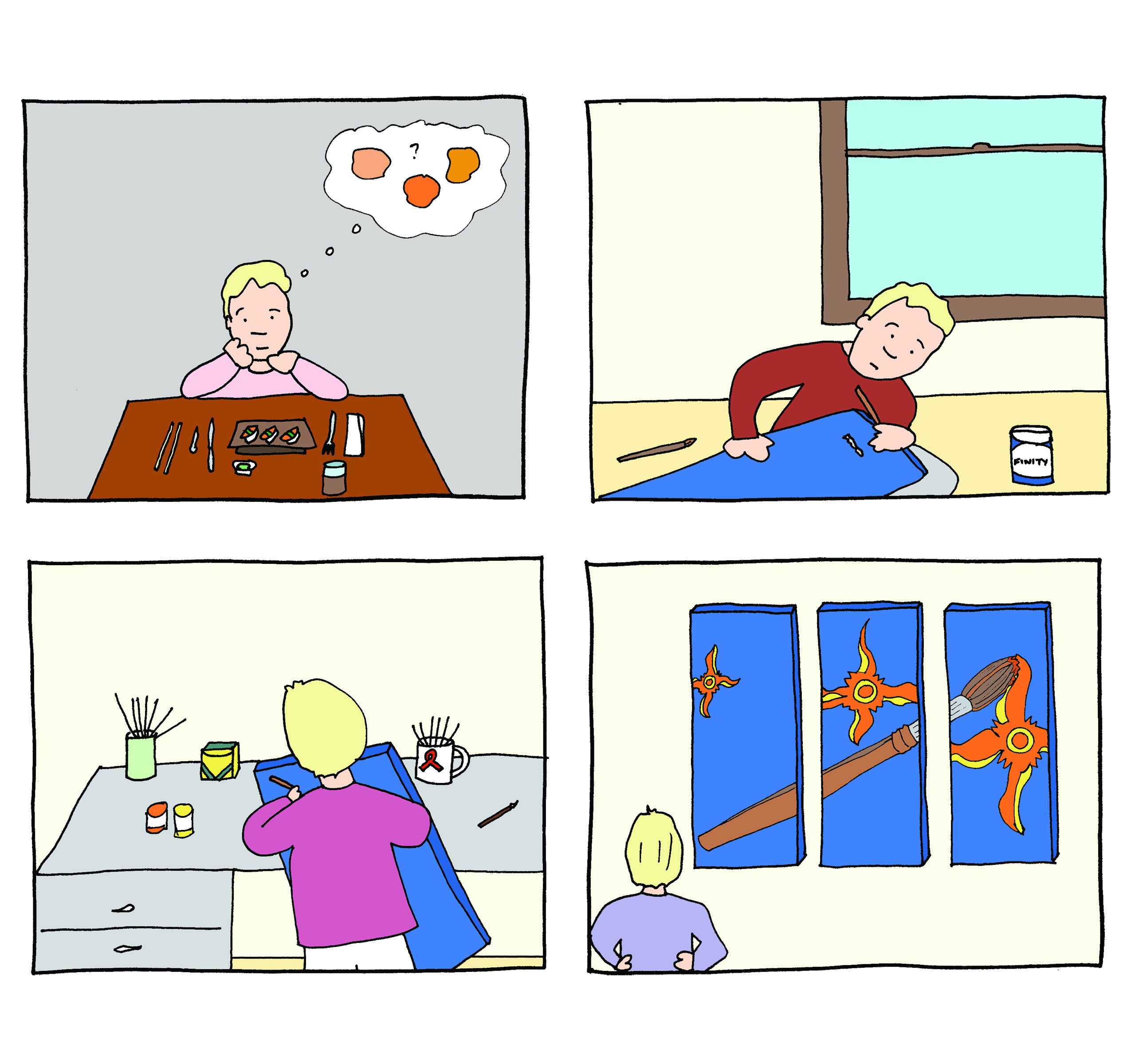

This afternoon, Czerwiec asks the students to take a pack of crayons and create a four-panel comic. The students have to work collaboratively: After filling in their first panel, they must trade off and pick up the story where their counterpart left off. One comic by Dan Im, a second-year Feinberg student, begins with him standing outside a patient’s door during his first day as an attending physician. When he meets his patient, he stumbles over his introduction, and is immediately consumed by doubt. The next panel reads: “WHAT DO I DO / WHAT DO I DO / WHAT DO I DOOOOOO.”

Other comics detail the tedium of waiting for samples to finish in a lab, what a “good death” might look like, and how to advise a patient on improving their diet (“counseling ≠ commanding”, it notes). For students like Im, it’s a way to discuss issues that recieve scant attention in other courses, particularly the anxiety and fear that can so often feel off-limits in the hallowed halls of science.

“Nobody in the class is very good at drawing,” Im says. “But we have a lot of fun – there’s no judgment involved.”

It’s also an exercise in thinking about perspective: How close are the students to a patient when they make a diagnosis? Do they keep their distance or loom overhead? What do they remember about the room they’re working in? Does it seem like a nice place to be?

Czerweic wants to remind the students about the details so they understand that their perceptions affect the way they take care of others. She wants them to attend to the story of both the patient and the provider. In short, it's an opportunity to ponder how the material they study in books applies to the world at large.

“They don’t practice technical skills on technical objects,” Czerwiec explains after the class. “They’re practicing on people.”

The name for what Czerwiec teaches is “graphic medicine.” But it’s something that humans have done for a long time – trying to make sense of the beguiling experience of illness, death, and dying. The ancient Egyptians wrote how-to instructions for mummification; Buddhists detailed the cycles of life, death, and rebirth in the Book of the Dead. More utilitarian practitioners include the U.S. Army, who created comics that explained the dangers of mosquitos and showed examples of how to effectively treat combat wounds during World War II.

Today, things are a bit different, if only because there’s more interest in graphic medicine than ever before. A few weeks ago, Czerwiec was invited to ReImagine, a festival in New York that explores questions around life and death, and hosted a pop-up magazine at the New York Public Library. The National Institutes of Health now hold thousands of comics about health and illness. Leading medical journals publish comics from doctors, nurses, and patients in their pages. The New York Times even reviewed a book Czerwiec contributed to last year.

One of Czerwiec’s collaborators is Alex Thomas, an allergist based in Chicago. He studied art theory and practice at Northwestern, and today he's part of Booster Shot Media, a company that educates people about the complexities of health topics through comics. He says graphic medicine is all about awareness.

“Perceptiveness is not something that was ever taught to us as physicians. We’d get feedback if we were doing good or bad on a rotation, but they were never teaching us to be more empathetic or more understanding,” Thomas says. “And who knows if there’s a more formal way of doing that – but I think that comics can help to encourage that introspection that can lead to greater empathy.”

Panels from Czerwiec’s book, “Taking Turns,” depict how art helped her to make sense of loss. /

Educating people on complex topics doesn’t mean making them easy, though. It’s on full-display as you read through “Taking Turns,” a comic that chronicles Czerwiec’s time working on Unit 371, Chicago’s first AIDS ward.

In one scene, she’s seated with a patient at a restaurant in Chicago, who asks her quite directly: “What’s it like when we die?” Czerwiec tries her best to answer. She’s tempted to base her response on past experience, but, in the end, she elects for something more ambiguous. It depends on what you’re dying from, and where you’re dying, and who's taking care of you and how badly you want to fight.

Okay, the patient says, that makes sense. But how can I know when it’s time to stop? And can you be there to tell me when it’s time to let go?

Czerwiec responds in the affirmative, but she’s also uncertain about how to address his questions – she spends the night driving around trying to decide what to say. In the end, her patient dies, and it's not pretty, poignant or graceful. He has a horrific panic attack, a nurse administers a dose of Ativan, and he never wakes up, though he stays on a ventilator for 10 days.

It’s not the kind of death you wish for someone you care about deeply, but there’s something beautiful about the way Czerwiec shares these events. You might not see the bright colors and bombastic interventions of the superheroes you expect to encounter in a comic, but the visuals are an emollient for difficult conversations, the sort that we don't like to have in our day-to-day lives.

“We’re all patients and there’s always danger,” Czerwiec says. “But comics are safe ... They are great at destigmatizing stigmatized things.”