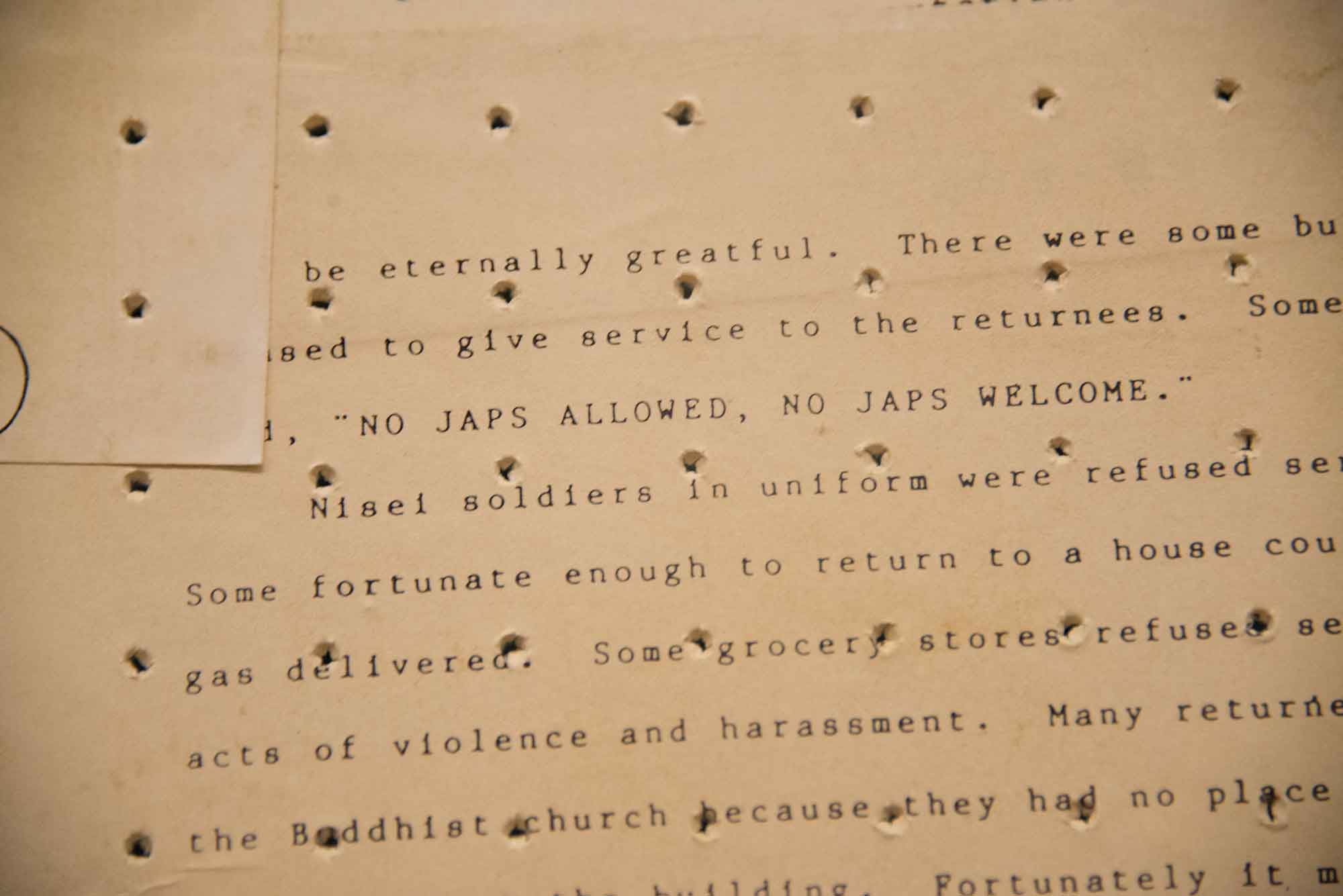

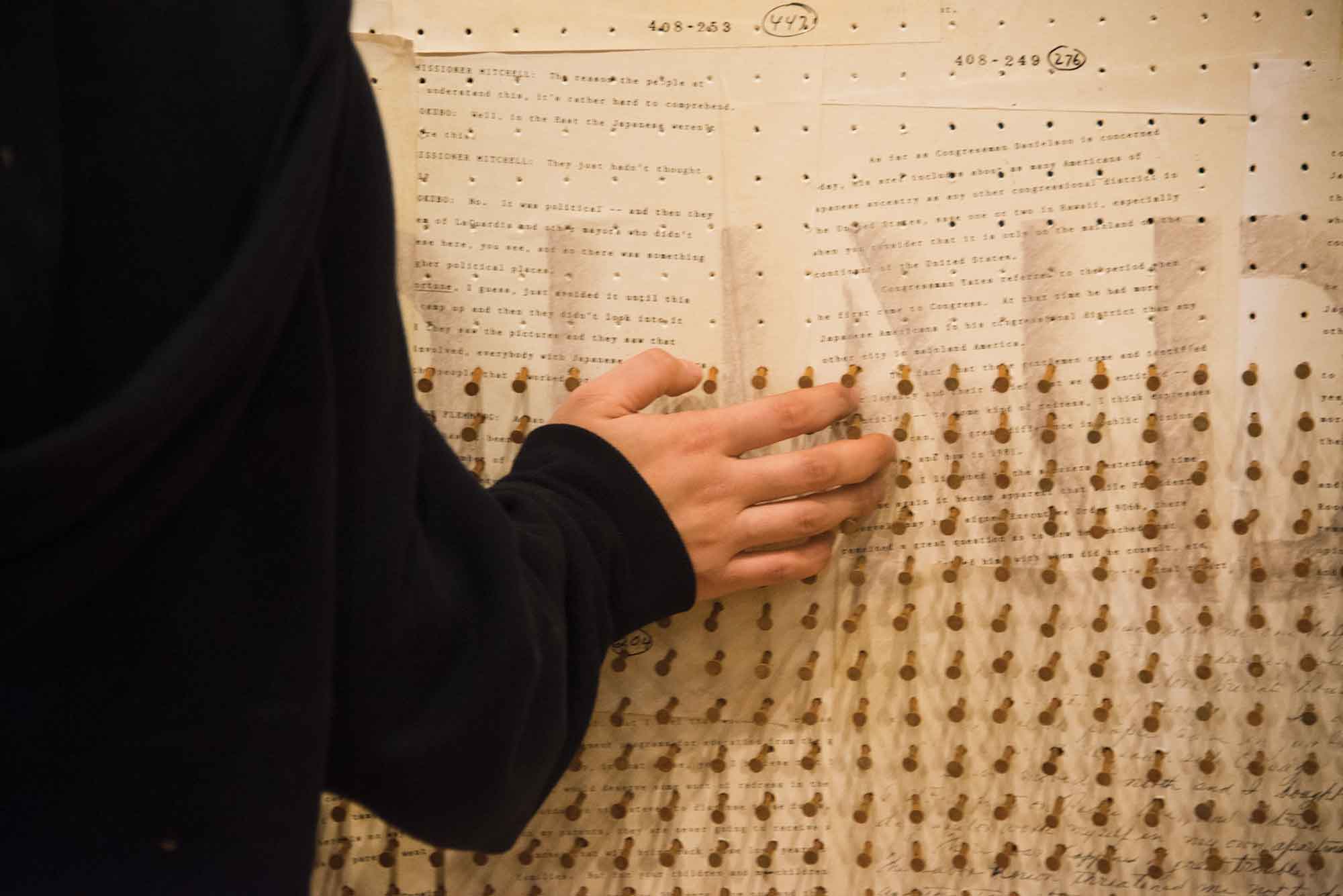

Kristine Aono’s American flag is not made up of nylon, polyester and cotton, but 65,000 rusty nails. Part of the Block Museum exhibition If you remember, I’ll remember, Aono, a Japanese American artist, created the installation “The Nail That Sticks up the Farthest...” to honor each Japanese American displaced by internment during World War II. The title of the piece comes from a Japanese proverb, Deru kugi wa utareru, which translates to “The nail that sticks up the farthest takest the most pounding.” Visitors participate in the exhibition by inserting nails into the pre-drilled holes in the wall to show solidarity and can even form words with the nails to express their own thoughts.

Aono’s piece came to the Block for the 75th anniversary of Executive Order 9066. Signed by President Roosevelt in response to the Pearl Harbor attack, the federal government forced Japanese Americans, mostly on the West Coast, into internment camps based on speculated connections to the Japanese Empire. They abandoned most of their material possessions and were subjected to manual labor, poverty and incarceration.

While the installation hopes to spark discussion about this often-obscured time in American history, it also offers a moment of reflection for Northwestern. In June 1942, a few months after the passage Executive Order 9066, then-President Franklyn Snyder banned the enrollment of relocated American students of Japanese ancestry.

Alex Furuya / North by Northwestern

During relocation, Japanese American students tried to transfer to universities in the Midwest, including Northwestern, because they could no longer go to school in their hometowns. Northwestern was one of the many of the schools that received these requests. Two girls wrote to the Dean of Women at Northwestern on May 11, 1924, seeking acceptance into “the University we so many times dreamed of...”

But the university did not entertain their request. In a phone call that June with the Chairman of Chicago Civil Liberties Commission, Snyder said the Board of Trustees had “reached our decision to not encourage such students to enroll at Northwestern.” Later, in a letter to the director of Japanese American Student Relocation, Snyder wrote that before the federal government could formulate a plan for distributing those students, Northwestern could not accept them, even though they were American citizens. It seemed that citizenship wasn’t enough to protect them from racial discrimination.

“I feel that Asian Americans are ‘perpetual foreigners,'” says Communication junior Yoko Kohmoto, who was born in Japan and moved permanently to the U.S. in third grade. “Even when I tell people I’m from Ohio, because of my look, people will always ask ‘Oh so where are you really from?’”

“I feel that Asian Americans are ‘perpetual foreigners.'”

Northwestern was not the only Midwestern university to side with the government. The President of the University of Minnesota wrote in the Minnesota Alumni Weekly that after consulting with 15 other universities, he realized all “were hesitant to open their doors wide, for fear that there would be a large influx of the western students.”

Over 500 institutions of higher education admitted about 3,000 relocated Japanese American students between 1942 and 1944. Universities and church boards provided scholarships, according to a letter the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council sent to Snyder in October, 1944. That year, Japanese American students were finally free to attend any institution, except for those on the West Coast. These schools still had to report applicants to the federal government, which decided their admittance on a case-by-case basis.

While Northwestern’s stance disappoints Kohmoto, she says she’s not surprised. Running a university is just like running a business, she says, and Snyder’s decision was probably to avoid confrontations with the government. Today, she says, colleges are getting more vocal and inclusive as a marketing strategy that evolves along with society.

“I think colleges were afraid to stand up for what is right because it could compromise their ‘business,’” Kohmoto says, “And that’s an awful reason to treat humans based on what was not under their control.”

Alex Furuya / North by Northwestern

Many students had similar harmful sentiments. A survey of Northwestern students in February 1942 showed that 9 out of 10 students favored bombing Japanese cities. 63 percent of these students favored all-out reprisals, which would have allowed the U.S. to bomb locations that were not military objectives.

Even today, Kohmoto suggests the recent removal of Dr. David Dao from a United Airlines flight speaks to how Asians are targeted because they tend to follow instructions without fighting back. It’s a sentiment Aono seems to share, at least in the context of internment.

“My generation would probably protest,” Aono says. “But [in 1942] for the most part, the [first and second generation Japanese Americans] went into the camps without resistance to prove that they were loyal Americans.”

But Ji-Yeon Yuh, a professor of history and Asian American studies at Northwestern, says things today are not radically different than the 1940s and obedience was not the reason Japanese Americans didn’t rebel.

“It’s not about being ‘naturally inclined’ to be submissive, it’s about being faced with no choices, about not really knowing what’s going on,” Yuh says. “In the 1940s, that specific fear of war with the Japanese Empire became a racist fear of anybody of Japanese ancestry. Today, the specific fear of a particular group of terrorists became the general racist fear of all Muslims.”

Amid the uproar caused by the travel ban signed by President Donald Trump, it’s worth remembering Executive Order 9066, still a relatively obscure part of American history. Bienen junior Noelle Ike says that growing up, she didn’t have much discussion about the internment in history classes. Her textbooks, she says, only give it a fleeting mention.

Alex Furuya / North by Northwestern

“I didn’t really understand the politics of it, and really how out of place it was even for that time,” Ike says.

Yuh says people rarely talk about the internment because it doesn’t fit the narrative of the American Dream.

“Internment tells a story about racism and that’s not a story to be told in America,” Yuh says. “The story told in America is the rise of American power to fight for democracy and freedom for everybody. And the story about Japanese Americans does not fit, so it doesn’t get told or it gets told as a little footnote.”

“Internment tells a story about racism and that’s not a story to be told in America. The story told in America is the rise of American power to fight for democracy and freedom for everybody. And the story about Japanese Americans does not fit, so it doesn’t get told or it gets told as a little footnote.”

And to many Japanese American students nowadays, racial differences are still a clear reminder of the disparity in American society.

“No matter how long I live here I don’t think that white America is going to see me as full American,” Kohmoto says.