Swim coach Tom Robinson invented the sport while working at the Evanston YMCA in 1907. During his early years on campus, water basketball spread from Chicagoland throughout the Midwest and eventually across the country. Chicago athletic clubs were among the first to officially adopt the sport. Meanwhile, Robinson began to stage water basketball “curtain-raisers,” or athletic opening acts, prior to Big Ten swimming events in Patten’s new state-of-the-art pool, exposing other schools to the new game. By 1913, the Big Ten Conference dropped water polo and made water basketball an of cial event at men’s swim meets in 1914.

The rules eliminated the underwater action and violence of water polo while retaining the fast pace and excitement of the game. Unlike in water polo, players could swim underwater, enabling trick plays and keeping defenders on edge. Each team had three defenders and three forwards trying to score baskets into hoops suspended above the water. Every basket earned one point, and games were quick, consisting of two 10-minute halves with a five-minute halftime.

According to a November 1912 Daily article, water basketball was, “on the whole, far cleaner” than water polo since only two players could battle for possession as opposed to the large scrums that develop in water polo. Players who didn’t have the ball could not be tackled. However, this “clean” characterization didn’t always hold true: the 1926 yearbook described the season finale between Northwestern and Iowa as “a first class dog fight... four Northwestern men were stripped of their shirts during the fracas while two Iowa men were taken out of the game because of injuries, one having to be taken to the city hospital.”

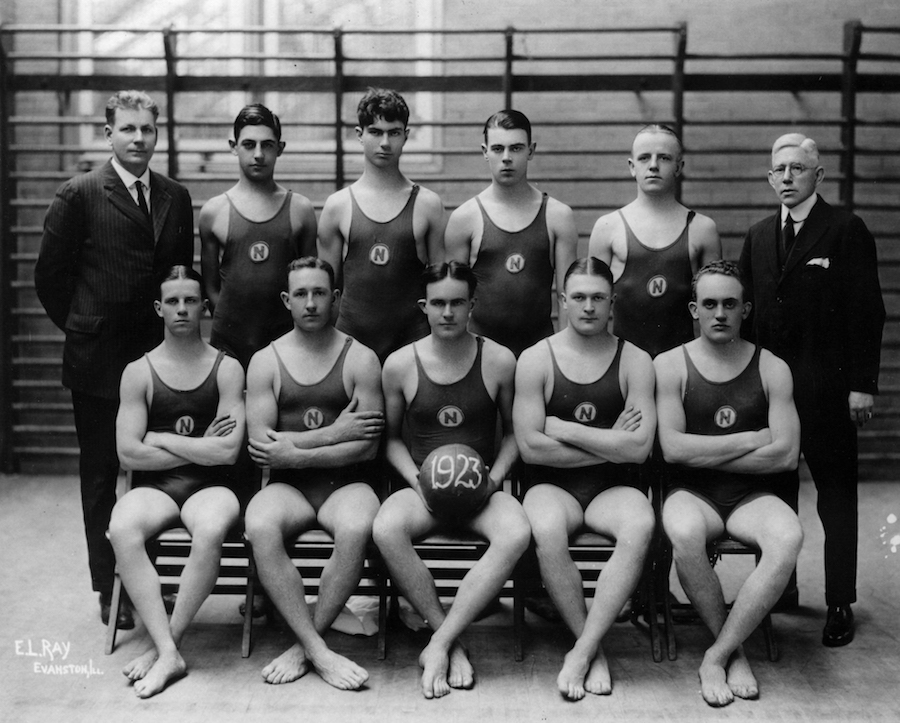

From 1914 to 1918, the NU water basketball squad outscored its opponents 166-55. In 1924, the only year that water basketball was a component of the NCAA’s intercollegiate swimming championship, Northwestern won. The next year, the Big Ten reinstated water polo and ended its 12-year water basketball experiment. Although popular among college students, water basketball did not catch on in high schools, nor was it recognized by the Olympic Committee, so conference officials decided that the international sport of water polo had a better chance at long-term success. Robinson supported the move and expressed the hope that “once developed... it will rank as great a place as water basketball has occupied in the conference in the past.”

The Patten pool is long gone, and so is the sport of water basketball. Now, all we can do is imagine the excitement of a self-created Northwestern sports dynasty. What water basketball lacked in longevity, it made up for in inventiveness and popularity on campus. And, let’s be honest: the real victory is that the Big Ten implemented the “rough, hilarious” sport at all. As Dr. Seuss would say, “don’t cry because it’s over, smile because it happened.”