Foster-Walker was only a year old when the first residents asked to move out in 1973, complaining of loneliness and isolation.

It was five years old when 20-year-old resident Jane Mitrenga killed herself in her car in the front parking lot of the building.

Plex was six years old when, in response to Mitrenga’s suicide, local PBS journalist Michael Hirsh featured the residence hall in his film College Can Be Killing. In it, he claimed the dorm had a reputation for contributing to students’ emotional problems and depression.

The building was seven when residents jokingly offered “special suicide rates” to a group of high school seniors visiting Plex on a tour, according to a 1980 Daily Northwestern article.

By 1981, the residence hall had come to “represent all that was grim and cheerless about Northwestern life,” said student Carl Briggs in a 1981 Daily editorial. It wasn’t even 10 years old.

Still, 60 students were on the waitlist for a room in Plex that year. Indeed, the University has never struggled to fill space since Plex’s opening, and while it may be the least desirable housing option for many upperclassmen today, it still accommodates about 475 students – 85 percent of its 560-person capacity.

While no longer nicknamed “Suicide Hall,” Plex still has a reputation for exacerbating – and in some cases causing – mental health issues. The exclusively single-style living, lack of community engagement and architectural structure work together to create, for a small number residents, a truly nightmarish, isolating living experience. For too many students, it is a bleak spot in their time at Northwestern; an experience they just need to get through.

Senior Lexy Praeger and her friends were not happy when they realized their priority numbers landed them in a suite on the third floor in Plex for their sophomore years, rather than in Kemper as they had hoped. They’d heard the rumors: Plex was depressing, filled with antisocial people who didn’t have anywhere else to go.

It helped to spend as much time as possible away from the residence hall, and gather in one of their rooms when they had to be home. But the single rooms still sometimes pulled them into solitude.

“If you get into kind of a bad cycle where if you’re upset or kind of depressed about something, it doesn’t force you to get out of that environment at all,” Praeger says. “It kind of just pushes you farther into it.”

Praeger felt trapped and cheated, especially because her and her friends’ placement in the residence hall was entirely out of their control.

“A number can kind of screw you over for an entire year,” she says. “Who knows how much that one number will contribute to your depression?”

At Plex, suite-style living means around five students share one bathroom, but otherwise have individual spaces. Each floor shares two lounges in opposite corners of the building. This encourages limited contact with other students, especially when a resident does not live near friends. But Plex was not originally planned this way.

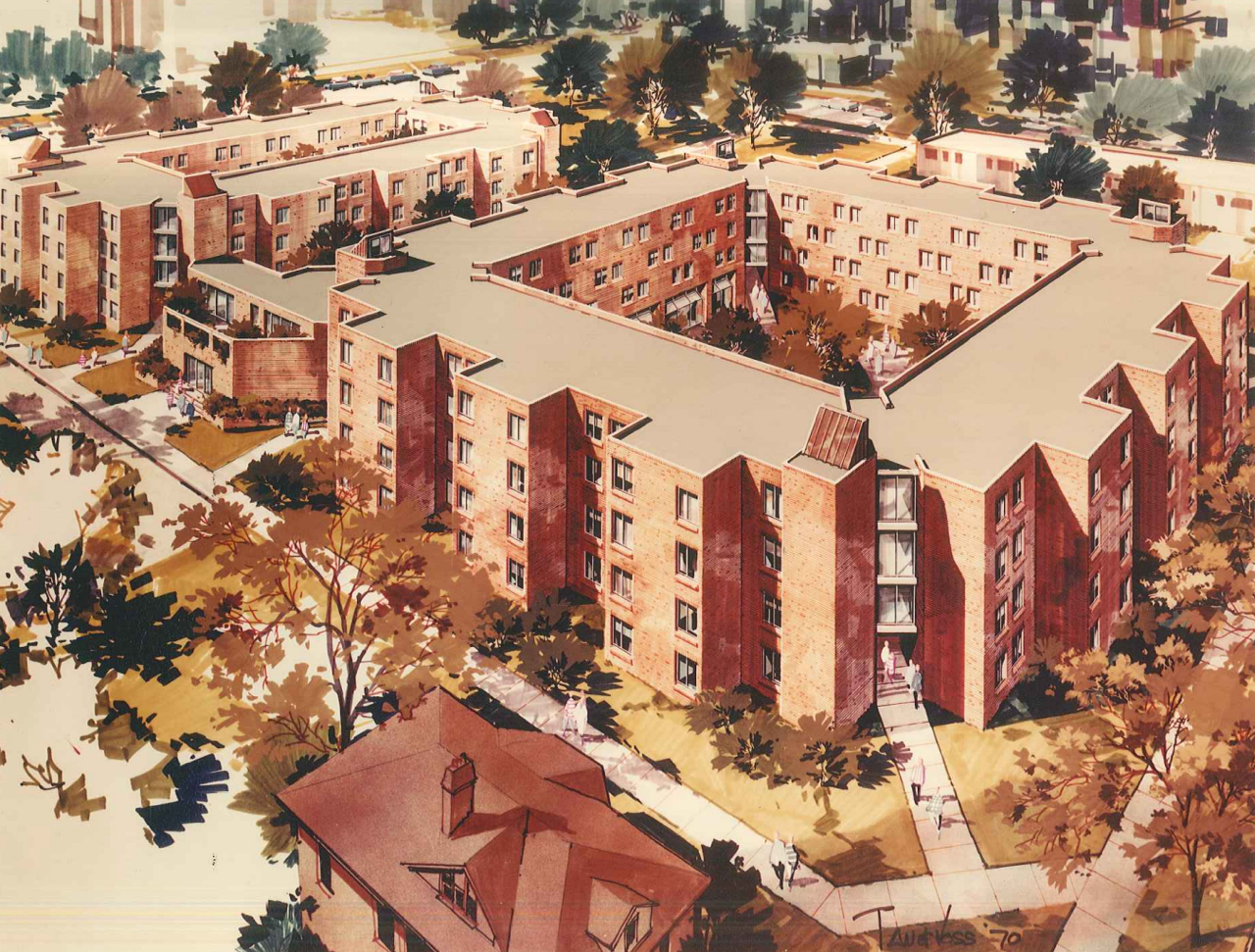

As undergraduate enrollment grew in the early 1960s, the University needed to accommodate a growing demand for on-campus housing. A committee proposed a mid-campus “living-learning environment” with a rich community and diverse housing options from singles to quads. But a high demand for single-occupancy housing prompted the design of a complex with entirely single rooms.

Initial proposals in 1964 planned for the complex to be two quads surrounded by four smaller “houses.” The houses would be separate, connected only on the first floor. The “vertical integration” would promote smaller, more intimate living communities.

A $2 million cost overrun led the University to alter its plans. The proposed nearly-separate houses became connected on every floor. The result – two large structures with 582 single rooms – promoted anonymity, rather than community, even though elements of the eight-house structure were preserved.

Paul Warschauer (Speech ‘76) was one of the first residents to move into the dorm in 1972. He and the other residents were thrilled to have access to all the amenities the ‘70s had to offer. Considered one of the “lucky ones,” Warschauer jumped into the social life of House Three: As secretary treasurer, he created programming that included a cabaret show and house outings to Chicago.

Other houses weren’t so lucky. After just a year, many students in other houses requested to move to House Three or out of Plex entirely.

“If you were not an A personality you were in trouble,” Warschauer says. “You had to make your own way because the only contact that you had was with somebody else who was sharing your bathroom.”

Today, just as it was in the 1970s, individual experience largely depends on what students make of it – even though Residential Services now works to provide community-building programming. Among residential assistants, it’s understood that those who choose to live in Plex may not be receptive to this type of social activity.

Plex can be the perfect place for people who have established social groups outside the building who don’t necessarily want the space where they live to double as their social space, says Huy Do, a residential assistant in the building for the 2016-17 school year.

For less gregarious students, the lack of community, strictly single-style rooms and shortage of common spaces can pose a problem. The structure of Plex allows students to enter, climb the stairs and walk to their rooms without passing a common area – or even a single person.

Structurally, the University has not significantly altered Plex since it was built 45 years ago, according to Paul Weller, director of planning at Northwestern Facilities Management.

But, per Northwestern’s Housing Master Plan, Plex is scheduled for renovation in 2022-23. While Plex renovation plans are not close to solidified, the University has budgeted $85 million to $90 million for the project, out of the $500 million allotted to the Master Plan as a whole.

Paul Riel, assistant vice president of residential and dining services in the Office of Student Affairs, oversees the Master Plan and its overarching goal of community formation. With “bold ideas,” Riel envisions Plex as a space based entirely around community, similar to what the University created in 560 Lincoln and the Mid-Quads. The building will likely remain single-occupancy, but more common areas on each floor aim to boost social contact.

Renovations may also include adding a fifth floor, enclosing the courtyards and making the first floor an entirely communal space. Riel proposes spaces like multipurpose classrooms, a cafe and a fitness center. These spaces, in addition to Plex’s mid-campus location, could drive more student traffic through the building.

“[These renovations] really are about community, and you need to bang into people and bump into people and trip over people in order to make that happen,” Riel says.

Still, changes to Foster-Walker are far from the implementation stage. The University needs to finish planned renovations at 1835 Hinman so that students can move there during Plex’s renovation. For now, Riel says Plex’s facelift is on schedule, but Hinman’s construction has already hit delays.

By 2023, Plex may be one of the best places to live on campus. But for the last 45 years, it has negatively impacted the experiences of countless students. For those residents, and students living there in the next few years, it stands unchanged, the same structure once dubbed “Suicide Hall.”