More than just a house

A symbol of hope and solidarity for generations of Northwestern’s Black Community.

By Naib Mian

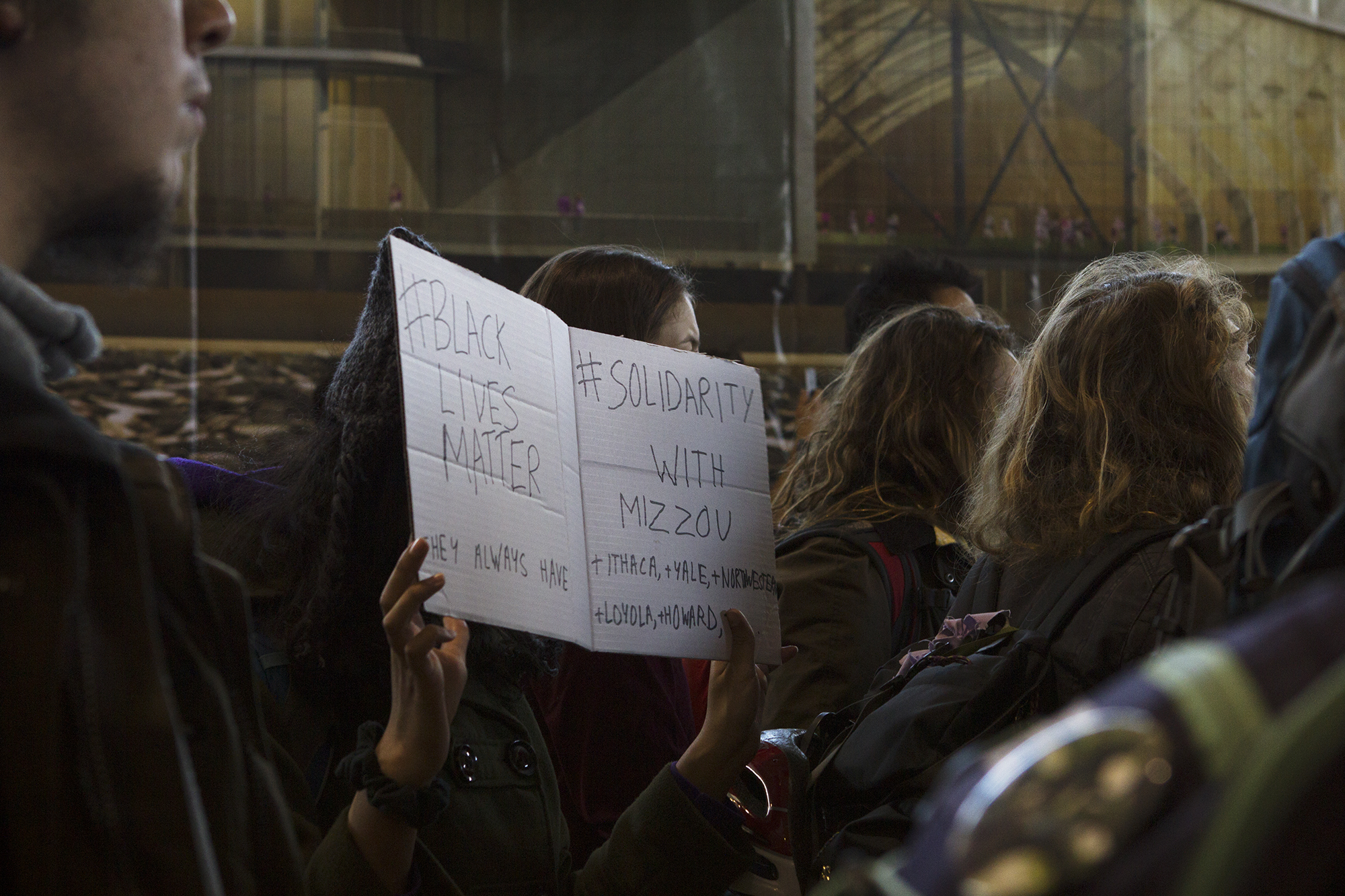

On Friday, Nov. 13, days after protests and racist threats flared up on the University of Missouri campus, about 20 Black students at Northwestern met at the Black House. They had decided a few days earlier that they wanted to stand in solidarity and advertised their action over a Facebook event page, where over 1,100 expressed interest in attending.

“I looked out the window and there were a ton of people standing outside,” SESP sophomore Michelle Sanders says.

The porch of the house quickly turned into a platform for voicing Black students’ frustrations. As momentum picked up, the gathering, about 300 strong, marched up Sheridan Road to Technological Institute.

Although prompted by the events in Missouri, they marched for more than Mizzou. They marched for Northwestern, for Black students everywhere, for Black lives everywhere.

Communication sophomore Sarayah Wright, who was part of the march, described it as both raw and thoughtful. Black cis, queer and trans women as well as femmes (those who do not necessarily identify as women but whose gender presentation leans toward femininity) were called to the front. “Those people are often erased,” she says.

Chanting slogans like “Mama, Mama, can’t you see, what Northwestern’s done to me,” students gathered in front of Tech before continuing to the Henry Crown Sports Pavilion, where a groundbreaking ceremony was taking place for a $260 million sports complex.

To the protesters, the ceremony demonstrated a lack of resolve by administrators to address issues that were important to them, pointing out the disconnect between which buildings the University chooses to renovate and which they do not.

“We could tell where the administration’s priorities were,” Wright says.

Students stood outside curtains that walled off the ceremony, directing their demands at President Morton Schapiro in an effort to disrupt the event.

“They ended up trying to speak over us and diminish that we were there,” Sanders says. “After a while, we got fed up, went through the curtains and took over the space.”

Wright and Sanders described audience members pushing and shouting, telling them to “go home,” “be respectful” and that “your time is up.”

“You don’t have to be yelling slurs, but we’re hearing the same thing,” Wright says. “You’re looking at us and seeing a violent, angry Black threat.”

After shouting their demands, attracting the attention of national sports media covering the ceremony, the protesters left, chanting, “You can’t stop the revolution.” They concluded their march outside by forming a healing circle, joining together to express support for each other.

“You look around and see each other celebrating each other – recognizing that us being here is revolutionary,” Wright says. “It was great to see each other fighting for belonging, fighting to be validated and heard.”

Resistance and Resilience

The history of Black activism is long at Northwestern – some students feel that their very presence here is resistance.

“Every breath we take is an act of liberation,” Wright says. The door for that existence was opened in 1883, when the first Black student was accepted to Northwestern, but a strict system of racial quotas limited numbers until the mid 1960s. Between 1965 and 1967, the number of Black freshmen registered at NU rose from five to 70.

By the spring of 1968, there were about 160 Black students on a campus of 9,000 graduate and undergraduate students. Facing failed promises of integration into campus life and hostile interaction with white students, For Members Only (FMO) and the Afro American Students Association, the representative organizations for Black undergraduate and graduate students, called for a voice in decisions being made about them. In April of that year, they sent a list of demands to the University administration.

The University refused to yield power to them, and on May 2, members of the administration invited students to discuss their concerns. Students had something else in mind.

The next morning, about 100 Black students entered the Bursar’s Office, the University’s financial administrative office at 619 Clark St. They chained the doors and participated in a sit-in. Over the course of two days, the students and administration underwent negotiations.

Students walked out the next evening having effectively pressured the administration to acknowledge the history of white racism at the University; create Black student committees to advise on financial aid and recruitment; provide separate housing facilities; and promise to set aside a recreational space on campus – the first step towards founding the Black House.

On Oct. 10, 1968, the vice president of student affairs released an implementation report on the Black Student Agreement that followed the sit-in. Included was the repurposing of 619 Emerson St. to include activity facilities, FMO meeting space, a library and study room, conference rooms, an informal lounge and a counselor.

This space would come to be known as the Black House, and in 1973 it moved to its current location at 1914 Sheridan Road.

“People think the Black House’s purpose is to be a hub for activism or subverting whiteness,” says Charles Kellom, director of Multicultural Student Affairs. “But that’s connected to how people understand blackness.”

The fight to establish and maintain that space, however, has influenced the collective memory and sentiment surrounding the space.

“It was meant to be a Black student union, a space to gather, but because of the ways in which it was fought for and how public that space is, it also serves as a symbol for the fight for equity and justice on campus,” says Lesley-Ann Brown-Henderson, Executive Director of Campus Inclusion and Community.

That history is not just one of progress to be celebrated but also one of violence that must be acknowledged. Creating physical resources on campus was not enough to remedy a history of racism that was embedded in the culture of higher education where white students were often openly hostile to students of color.

“It was not uncommon to have trash and pop bottles thrown at you when you walked down Sheridan Road,” says Ce Cole Dillon, a 1978 SESP graduate who served as president of the Northwestern University Black Alumni Association. “The majority of students felt like they had the right to say: you’ve invaded our world, and we don’t want you here.”

Although this kind of blatant racial violence is less common now, Cole Dillon says the basic systems and implications are the same. “This sense of entitlement, that ‘you are here at our grace,’ it has lessened, but it hasn’t gone away,” she says.

Northwestern’s Black House therefore stands not only as a site for activism on domestic and international issues but also as a salient symbol worth defending in and of itself – a symbol of cultural resistance and resilience. As the 50th anniversary landmark approaches, perhaps the greatest tribute, as well as reminder of how far the University still has to go, is the ongoing action of students on campus.

Administrative changes meet student pushback

This past August, as part of its restructuring, CIC announced changes to the Black House and the Multicultural Center to renovate certain areas, move in staff offices and consolidate student group spaces. CIC had recently expanded to include Multicultural Student Affairs, Social Justice Education and Student Enrichment Services.

In an effort to consolidate the staff of these departments, Brown-Henderson says co-locating in one or two spaces would help them stay in contact and hear the experiences of students first hand.

With budgets allocated on a September to September fiscal year, Kellom says a significant portion was saved up by the summer, the end of the budgeting year, presenting them with the opportunity to pursue the alterations. But for students and community members, the timing felt like an opportune moment to circumvent them while they weren’t on campus.

“They presented the changes in a way that we wouldn’t know the damages to the communities served,” Sanders says. “It seemed like there was nothing we could do.”

The process represented a typical approach that systematically overlooked them. Black students and alumni held a conference call the day after the changes were announced.

“There was a blatant disregard for our reaction and input,” Wright says. “The main issue was how it undermined our relationship with the Black House.”

Kellom, who became director of MSA less than a month before the changes were announced, says they made an effort to vet the ideas and inform the community, but not many students participated in the Google Hangouts held on the proposed changes.

“It makes perfect sense that students felt their voices weren’t included, and I was sorry for that,” he says. “No one wanted to exclude student voices, but this seemed like one of those situations where people didn’t really pay attention until they felt like there was a problem.”

Given the response to the proposed changes, Kellom hopes to implement a more effective institutional system for students to provide feedback to MSA.

There is a history of administration overlooking the needs of marginalized students, says Brown-Henderson. Although she understands the sentiment, she says their intentions were incorrectly perceived as malicious.

“What we’re saying is trust us,” she says. “I’ve tried my best to push forward our equity and inclusion. Some of that has been behind closed doors where no one sees, but it’s clearing the pathways for students to be able to express themselves,” adding that much of the work she and her office does is aimed at creating incremental systemic change.

And they did, taking to social media channels to decry the alterations, which they felt prioritized administrative duties over student experience.

Four days after the announcement, MSA decided to suspend the planned changes and organized four listening sessions for Fall Quarter to be followed up by a Black House Facilities Review Committee made up of students, faculty, staff and alumni.

But these sessions fell short for many students.

“The administration said things like: ‘We’re not gonna do these changes, and we’re not going to talk about that. Say what specific things you want to see in the Black House,’” Bria Royal, Communication senior, says. “They made it seem like an isolated incident but it’s not. This is part of a larger narrative – the spaces of people of color being diminished to the tiniest piece.”

“No amount of coats of paint on the walls will fix the institutional racism,” she says.

Cole Dillon, who represents Black alumni on the review committee, says she is hopeful the recommendations will come from an organic place, but she recognizes the University has no obligation to accept the suggestions.

“Based on what we heard and what we know of our own experiences, we have a perspective on where we think the future of the Black House lies,” Cole Dillon says. “It can’t possibly be to just have a sign on the building that says the Black House and the function is just like any other administrative building.”

Beyond coats of paint

For students who use the space, it clearly is not any other administrative building. In an effort to follow through with their action in November and in response to the University’s proposed changes, students released a set of demands, just like their predecessors had almost 50 years ago, to improve the climate on campus for Black students and other marginalized groups. One portion of these demands focused on physical campus spaces like the Black House, calling for updates to software in the computer lab and more resources for STEM students of color.

But the demands go beyond surface level changes, and students and staff agree that is necessary to more effectively improve Black student life.

“Improving the Black House isn’t enough to change campus climate or culture,” Kellom says. “That’s about educating the entire community: things like the diversity requirement that’s focused on U.S. social inequalities and training faculty and staff. There’s a multitude of things, addressing things like the attitudes, values and the University’s history.”

Sanders, who has been closely involved with the accumulation and writing of the demands, says they haven’t limited themselves in scope. Their goal is to express sincere demands without concern for what administration considers realistic and unrealistic.

“Basic rights and resources shouldn’t be that hard to implement,” Sanders says. “Having staff that looks like you is not unreasonable.”

After a wide-scale campaign of emailing the list to President Schapiro on Black Friday, students heard back in December. In an email co-signed by Schapiro, Provost Dan Linzer, Vice President of Student Affairs Patricia Telles-Irvin, Executive Vice President Nim Chinniah and Associate Provost for Diversity and Inclusion Jabbar Bennett, students were asked to select five or six representatives to meet with the administrators in January, again bearing resemblance to the events of 1968.

“The idea of meeting with five or six students didn’t sit very well with us,” says Weinberg senior Thelma Godslaw, who attended the meeting. “The demands concerned a lot of communities and individuals, so we invited everyone to come.”

On Jan. 7, Black Lives Matter NU hosted a townhall for concerned students to share their own ideas and collaborate across a wide range of communities to make the demands as comprehensive as possible before they were taken to the administration.

“You see how the Black Lives Matter movement has become more intersectional than the original civil rights movement,” Godslaw says. “We wanted to make sure the demands were intersectional and aware of the other communities on campus, that they encompassed the broadness of Blackness while showing solidarity.”

The Weinberg senior says about 10 students came to the meeting with the five administrators. Held on Jan. 19 in the Black House, students gave the administrators an updated list of demands; asked for monthly follow up accountability meetings and a website to detail concrete progress on the demands; and used the space as an opportunity to air grievances.

“We wanted to control the space in the sense that student voices would be prioritized and not just administrators telling us what they accomplished,” Godslaw says.

Telles-Irvin followed up with some of the students two weeks after the meeting, announcing the creation of a website, Inclusive Northwestern, that will feature updated responses to the demands and dates for upcoming “community dialogues.”

Khaled Ismail, a graduate assistant in MSA, says staff and students in multicultural offices play a large role in influencing change from within administrative structures of higher education, which doesn’t naturally recognize inequity.

“Our role is to advocate for students here,” he says. “We are the change agents from within. Students play an important role in change from the outside.”

For Brown-Henderson, that work is pressing but takes persistence.

“The students who I work with, seeing their pain, their experiences, the detrimental impacts of oppression and what that does to the soul, it’s a hard pill to swallow,” she says. “We have to do something to change it – not to band-aid change it – but to systemically change it.”

Through her work, Brown-Henderson strives to fundamentally change the experience of students of color.

“What would it look like for our marginalized students to see their experience woven into the culture of this institution?” Brown-Henderson says. “It’s a marginalized student saying, ‘I thrived here at Northwestern.’ It’s a student who feels as comfortable in Norris or their residence hall as they feel in the Black House. It’s a University where the faculty and staff are reflective of the student population.”

That work involves going beyond facilities updates and construction of student spaces. The student demands go beyond these surface level improvements, and their authors hope to elicit a serious response from the University administration.

“It’s not as simple as putting together a wishlist of items and putting them in a house and calling it a day,” Royal says. “Producing more systemic change will take some effort on the administration and the faculty to acknowledge the kind of environment where these kinds of daily oppressions are happening.”

A safe space and so much more

It is in the midst of this current environment that the Black House offers a form of refuge to Black students. For Royal, seeing the Black House during her first visit to Northwestern was instrumental in her decision to attend.

“I remember going through the whole tour and barely seeing any students of color,” Royal says. “We had some free time, and I remember coming here with my mom and being like, ‘Oh, there are people of color here.’ I remember that moment being like, ‘Maybe I can come here.’”

Although the House serves as a shelter for students like Royal, she takes issue with discussion surrounding safe spaces.

“We need to commit to centering the narrative on the people who are most at risk in this situation,” she says, addressing a recent op-ed in the Washington Post written by President Schapiro. “When I first saw that article, I noticed it was titled ‘I’m Northwestern’s President.’ What does that say right there?”

Schapiro declined to comment on the article, saying his views on safe spaces were clear.

At the end of the day, students are asking why the only safe places for them are pinpointed and the responsibility is theirs to protect those spaces rather than the University’s as a whole to improve.

“Who are the powers at hand that are making it so that we need a safe space,” Wright says. “The conversation always revolves around us instead of ‘what are you [the university] doing that’s making this a problem?’”

While recent campus activism has focused on the Black House as a historic place of refuge worth defending, Royal doesn’t want that to belie the larger issue, which is institutional.

“The administration is looking at this as an isolated issue,” she says. “But why is it that we have refuge spots for every marginalized group on campus?”

One of the causes of concern with the proposed changes in August was the further consolidation of spaces for students of color. Four cultural student groups would share the top floor of the Multicultural Center under the planned adjustments to open up more offices.

“We’re not dealing with the same issues,” she says. “There are distinct differences in oppression, and ‘people of color’ as a term lumps us together despite our unique engagements with oppression, white supremacy and patriarchy.”

This lumping of marginalized identities is historically institutionalized, and that process has occurred on Northwestern’s campus as well. Cole Dillon describes how the United States was a Black-white duality until the 1970s and 80s, when other ethnicities began to come with their own needs.

“The University focused on the similarities of people of color rather than trying to understand how these groups are different,” she says. “You had to give up who you are to acquire Northwestern.”

In an effort to resist that erasure, the Black House acquired another role – preserving culture.

“There’s a much larger context to the Black House than just a safe space,” Cole Dillon says. “It historically served as a cultural space. Our history, our culture, none of those things do we want to leave at the front door in order to become Northwestern students.”

Traditionally that has meant facilitating student-faculty interaction and hosting significant members of the Black community and jazz and blues musicians. More than just a resource center or student union, the house is a place where they can learn from upperclassmen, learn about a complicated history and culture or simply engage in recreational activities.

“I’m all about creating a safe space for people to talk, but I’m also a strong proponent of a brave space, where you feel compelled to participate and act,” Royal says.

For many Black students, the Black House is a centerpoint for student life in all that that entails; labeling it as a safe space essentializes what takes place there.

“We’re complex,” Wright says. “It’s a safe space, a place of celebration, a place to be and to talk to your friends, a place to take naps. You can have a healing circle and then go to B.K. at 2 a.m.”

The Black House fosters bonds between those who frequent its halls. Ismail, whose office is also in the house, says it also ties its present-day community to the generations that laid its foundations and passed through the space.

“Each generation of students that have come through have a different experience in this space,” he says. “But this space connects every generation of students. There’s a common thread between all students who engage with the Black House. A common thread of belonging, of community, of a safe space. That’s how it preserves history – through that common thread.”

A symbol of hope

The house has withstood the test of time, its walls held up by the never-ending work of students who have carved out a space for themselves on a campus that, for so many of them, has only attempted to erase their history, identity and experience.

“This University was not created for us, plain and simple,” Royal says. “This house is a symbol of our resistance to all of that. Our continual resistance. When that’s threatened, it’s a reversion, trying to undo all the work that’s been done.”

The effort students put into creating and preserving the Black House reverberates through the space, a structure that has come to embody the struggle of Black students to simply exist.

“It was always that symbol of hope,” Royal says. “Maybe I can survive this place, even though it’s so vicious sometimes, if only I have this community behind me.”