Many people believe that vegans and vegetarians are severely lacking in protein, that gluten-free diets are hip and slimming - the list goes on. Generally, many of these thoughts are misconceptions, and often play a much smaller role in special diets than people assume. In everyday diets, the aggregate amount of daily calories that an average person needs is relatively low, and a few missing grams of protein will not severely impair body function.

However, for someone who uses more than an average amount of energy each day, these values become significantly more impactful. The true test to whether these special diets are feasibly sustainable and healthy for common, everyday regiments comes in seeing whether high-performing student athletes can live - and eat - by them. Katie Knappenberger MS, RD, CSSD, ATC, Northwestern Athletics' coordinator of performance nutrition, works to ensure athletes with special diets meet their daily nutrient and energy needs.

On top of early morning and late night workouts and competitions among, the athlete's body is a well oiled temple, meant to function at top shape both on and off the field. But what they put out and how smoothly they function depends on what they put into their bodies. The first line of critical analysis is the overall calorie demands of a student athlete. The USDA's recommended daily calorie intake for a moderately active college-aged person is around 2800 for men and 2200 for women. To maintain your weight, the calorie expenditure must be approximately equal to the consumption. For weight loss, the expenditure must be greater than the consumption, and for weight gain, the expenditure must be less than consumption. Comparatively, some student athletes expend up to three times the amount of daily calories than the average college student. According to Knappenberger, the lower end of calorie expenditure for college athletes is around 2500 while the high end is around 6000. Of course, the amount of calories an athlete is burning depends on their size, the percentage of muscle in the body and the intensity of exercise. For example, a football lineman like J.B. Butler would fall on the upper end of the spectrum for energy expenditure.

Manon Blackman and Sophia Stoughton both run. One as a triathlete, and one in Northwestern club track. They both expend an average of almost 2000 calories every day through exercise alone. These calories account for running, weight-lifting, strength-training and stretching. Blackman has been a vegan for two years and an athlete for over seven years. Stoughton has been fairly athletic her entire life, but became a vegetarian when she was 12-years-old, around the same time that she started running.

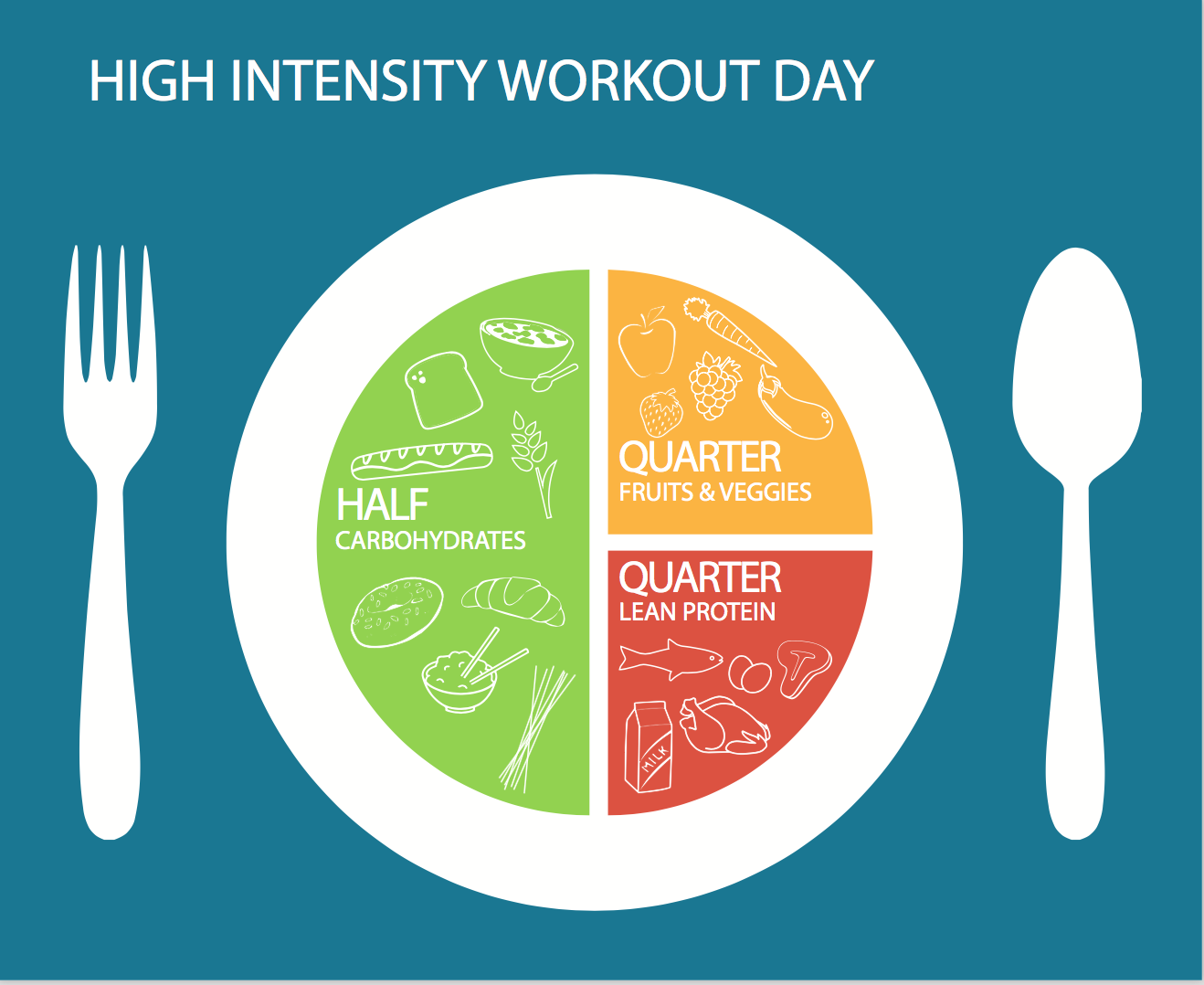

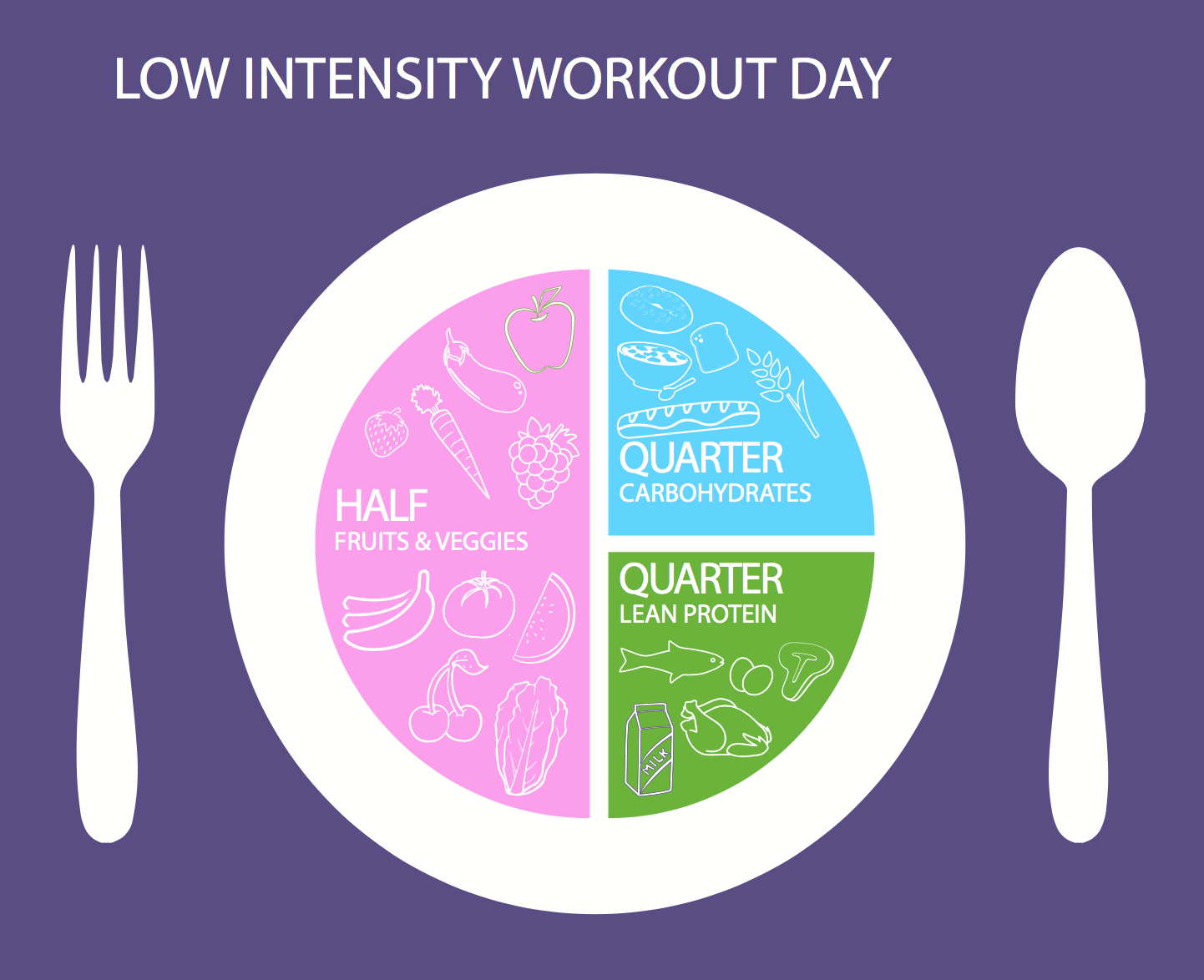

Graphics by Savannah Christensen

Post-exercise is where the energy recovery happens, and replenishing the calories lost during exercise is crucial. On occasions, athletes' meals are planned out for them, but most of the times, they are in charge of their own food. Knappenberger says the athletes at Northwestern go through an intensive nutrition education program that teaches students to alternate their intake of fruits, vegetables, carbs and proteins based on a day's work. On high-intensity workout days, the recommendation is for half of the plate to be carbs, a quarter to be vegetables and fruits, and a quarter to be lean protein. On an off-day, when athletes are doing mostly stretching, yoga or low-endurance, low-intensity exercises, the plate would look very different. It would be a quarter carbs, half fruits and vegetables, and a quarter lean protein. The off-day plate more closely resembles how the plate of an average person (should) look as recommended by Federal Occupational Health. The sheer volume of a regular athlete's plate astounds many people, and that volume is increased for athletes with special diets. Many commonly available foods allow for a higher density of easily accessible proteins, carbs and nutrients than would foods for special diets. But when it comes to these diets posing challenges and hurdles to athletic rituals such as carb-loading before a huge competition and protein-loading to recover post-competition, Knappenberger said that it shouldn't.

In fact, she said that there are a wide range of diets across members of the NU athletic community and they span all types of sports, including vegan female athletes, vegetarian male athletes, lactose-free strength and power athletes and lactose-free endurance athletes – to name a few. Stoughton and Blackman agree. Both say that they have not found it challenging to properly fuel up.

According to Knappenberger, the challenge comes for students who are under-prepared and under-educated. Athletes who are on vegan and vegetarian diets need to eat higher volumes of a wide variety of foods to meet the same energy demand. For example, the amount of protein available in one piece of chicken breast can be supplemented with two cups of chickpeas. Gluten-free athletes can carb-load on rice, quinoa, flax, corn and potato as alternatives to pasta and bread.

All in all, depending on their diet, these athletes need to consider their fuel a little bit more than your average athlete. "We are in an environment that doesn't always lend itself to help them, so they need to be planning ahead, packing their own foods, looking at the menu before going to a restaurant," Knappenberger said. "We don't want them to under-fuel, which is always a risk."

Stoughton said that she eats more plant-based carbs than most of her teammates, and more food in general than her teammates. She has maintained a healthy weight and doesn't have trouble building muscle.

"If you are eating mostly whole, unprocessed foods, a varied diet, and you are eating enough, then you don't need to worry about getting your essential nutrients and staying healthy. A lot of people use veganism as a weight loss tool and won't eat sufficiently, then when they are deficient they blame it on veganism," Blackman said. She additionally notes that given she watches her diet, especially before and after an intense event such as running a marathon, her body tends to recover better than it did before she was vegan.

Under-fueling is only one aspect: these athletes also must consider their vitamins and nutrients, a vital and even more tedious aspect to maintain. Two of the most important vitamins and nutrients athletes need for high performance are creatine and vitamin B-12. Most of the sources for these two nutrients come from meat, since they are not as bioavailable from plant sources.

Creatine is found in the muscle and is a crucial factor that aids in energy production during high intensity exercises. For the science nerds, this is what helps produce ATP molecules in the body. Vitamin B-12 helps to keep the body's blood cells healthy.

Most humans get their creatine from meat, and their B-12 from fish, meat, eggs and milk. "We recommend [blood tests] sometimes, because being vegan and vegetarian could put you at risk for iron deficiency, vitamin D deficiency, vitamin B-12 deficiency, and we want to exercise caution," Knappenberger said, adding that most athletes are already at risk for iron deficiency. Among many other reasons, this means extra education is required for these athletes. In addition, they are recommended to talk to NU dieticians about their eating plans.

"It all comes down to the amount of calories they need. The more food they need, the more of a challenge it is sometimes," said Knappenberger.

This is why the nutrition team has to work with the athletes to tackle these more tricky parts. If the athletes do use a vegan meat substitute to replace meat in their diet, it's usually fortified with vitamins which helps. Cereals and multivitamins, which both Blackman and Stoughton take, can also be beneficial. Otherwise, nutritionists have to get really creative to combine beans with grains and pull from all kinds of different food groups. The athletes have to sit down and work with certified dieticians to talk over what they need to do. A common myth is that these diets are all healthy, but Knappenberger said that you can have an unhealthy vegetarian diet or vegan diet as well if you're not eating everything you're supposed to.

Knappenberger acknowledges that a lot of these special diets are linked to medical conditions, such as lactose intolerance or gluten intolerance, and in these cases the diet plans are really appropriate and necessary. She does express concern when people try out diets that are trending, such as going gluten-free.

"If it's not linked to medical condition, we have to be careful of it masking things such as eating disorders. A lot of our athletes have eating disorders," she said. This isn't uncommon, either: NCAA even published an article to warn and safeguard student athlete mental wellness. "You can declare yourself vegan or vegetarian as an easy way to cut out food. If you're gonna subscribe to an eating plan, know your why and own your why."