One night this past October, Emily walked into the room where her close friend was attempting suicide. After saving their life, Emily and a counselor at the Center for Awareness, Response, and Education (CARE) helped her friend schedule an appointment with CAPS. Emily had met with a CARE counselor shortly after helping her friend. The counselor recognized Emily’s vomiting and inability to sleep as symptoms of post-traumatic stress.

“Probably the most helpful thing I have gotten from CARE or from CAPS was that she explained to me biologically what was going on,” Emily says. “So I stopped feeling weak about my trauma responses. Because it’s biology, and it’s not my fault.”

Emily, the counselor reasoned, was in need of short-term counseling - of someone who could help her work through the symptoms of her post-traumatic stress until the worst of it had passed. That’s how Emily initially got referred to Northwestern’s Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS).

“[The counselor] was like, ‘you’re still exhibiting signs of PTSD and trauma, and you’re still having biological trauma responses to some extent,” Emily says, “and I think you should see someone at CAPS.”

At her intake appointment, the CAPS counselor who Emily met with told her that while she would be an ideal candidate for CAPS’ treatment model, the long waitlist for individual therapy meant that she should probably seek outside treatment. But Emily’s health insurance left her with a high deductible and costly copays which Emily and her family could not afford.

After several weeks of waiting and frustrating attempts to navigate low-cost off-campus therapy options, Emily was eventually offered a spot off the waitlist at CAPS.

Bad Reputation

While it’s impossible to know how many students have experiences at CAPS resembling Emily’s each year, her story is far from an aberration. Over the past several years, students have frequently voiced complaints about the availability, accessibility and effectiveness of Northwestern University Counseling and Psychological Services.

“I feel like it’s a failure on the part of the University to recognize how big of a problem this is,” says Medill sophomore Alex Schwartz. In April, he penned an editorial in the Daily Northwestern titled “NU is grossly underfunding students’ mental health services,” in which he recounted his experiences being turned away from group therapy at CAPS earlier this year due to a limited number of spots.

“I was disappointed,” Schwartz says. “Obviously, this is a resource that students are told about coming in to Northwestern. You’re constantly told every time an event occurs in the national news, or there’s a student death on campus, they always tell you, ‘Go to CAPS. Go to CAPS, they’re here for you.’ And then, when you finally do decide to seek them out, you’re basically told that there’s not enough room."

Frustration from the student body over CAPS’ perceived ineffectiveness reached a boiling point in the spring of 2015, when McCormick junior Jason Arkin killed himself in his dorm. He was the second student to commit suicide that school year, after the death of Weinberg junior Avantika Khatri. In the weeks following his death, reports from the Daily revealed that Arkin had been referred to a waitlist for therapy at CAPS after discussing his thoughts of self-harm with a CAPS staff member.

Arkin had struggled with depression and anxiety throughout his life. He first reached out to CAPS in fall of 2012; his family noted in a letter to the Daily that he had been given the option to be put on a waitlist for individual therapy at CAPS, or to seek outside treatment.

“(CAPS) asked this freshman who was just getting ready to start his first final in the fall of his freshman year to go out and get help on his own,” Arkin’s father, Steven, told the Daily in 2016. “That’s where the big disconnect is … You can’t get in the front door on the first try.”

In the wake of Jason’s death, CAPS faced heightened scrutiny from students, many of whom lobbied criticism at the “12-session limit,” that capped the number of individual sessions a student could be seen for at 12. The following spring, Christina Cilento and Macs Vinson, the 2016-2017 Associated Student Government president and executive vice president, made the 12-session limit a central policy in their campaign pillar on mental health, with the plan by CAPS to eliminate the limit already in the works.

In response to the controversy, a task force comprised of the Dean of Students, CAPS staff and student leaders was formed in fall of 2015 to re-evaluate CAPS’ policies. In April of 2016, Patricia Telles-Irvin, Vice President for Student Affairs, announced via email that CAPS would eliminate the session limit based on the findings of the committee.

“That number, 12, was indelible in people’s minds, including [those of] my staff, so what we wanted to do was remove that barrier,” says John Dunkle, CAPS’ executive director. According to Dunkle, the elimination of the 12-session limit stemmed from concerns that students would hesitate to seek treatment at CAPS in their freshman and sophomores years for fear that they would need counseling later, after having already reached the limit.

But according to CAPS’ 2016-2017 annual report, the elimination of session limits did not change the average number of sessions per student at CAPS.

While the elimination of the 12-session limit was widely considered to be a step in the right direction, CAPS continued to court controversy; in September of 2016, Northwestern announced it would disband the long-term individual counseling run through the Women’s Center to redirect those personnel resources to CAPS. The decision outraged many students and alumni who believed that the Women’s Center provided more effective and accessible counseling than CAPS’ services. Shortly after the announcement, a Tumblr blog called “Save NU Women’s Center Counseling” was created, featuring testimonials of the Women’s Center counseling services from current and former students.

In the three years since Jason Arkin’s death – three years in which the Northwestern community would also come to mourn the deaths by suicide of Weinberg senior Scott Boorstein, Weinberg sophomore and women’s basketball player Jordan Hankin and SESP junior Kenzie Krogh – no substantive changes have been made to CAPS policy beyond the elimination of the 12-session limit and the absorption of Women’s Center’s counseling responsibilities. But confidence in CAPS remains low among the student body, and given stories like Emily’s, it’s not hard to see why. So what, exactly, is the problem with CAPS – and how can it be fixed?

Beyond the 12-Session Limit

Behind the desk in his office on the second floor of Searle Hall, where CAPS is housed on Northwestern’s Evanston Campus, John H. Dunkle leans forward intently, placing his glasses down on the desk and putting them back on with a rhythmic regularity. Dunkle joined the staff at CAPS in 1995 as a staff psychologist, directly after his pre-doctoral internship at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Prior to this, he received his Ph.D. at the University at Albany, SUNY working as a counselor at SUNY Albany; in 2005, he took over as Executive Director from his predecessor, Dr. Kathy Hollingsworth.

CAPS has always functioned as a counseling center primarily focused on brief, skills-based treatment, in keeping with the norm at counseling and mental health services at universities across the country. According to Dunkle, the short-term treatment model is based in empirical evidence for effectiveness from organizations like the Center for Collegiate Mental Health.

“What I hear and see from [national surveys], is that the vast majority of counseling centers are brief,” Dunkle says. “There’s a lot of great research out there on the efficacy of brief treatment. You can accomplish a lot within six to 10 sessions, believe it or not. So what a lot of universities are doing is, they’re trying to meet the needs of as many students as possible, and in order to do that, you have to have some type of a plan for brief treatment.”

“Whether or not we have a session limit, the vast majority of students get their needs met within six to seven sessions,” Dunkle says. “There are some who would definitely benefit from more, in which case, now that we’ve eliminated session limits, we come up with an individualized plan for each student. The beauty of this approach is that each student gets an individualized plan.”

According to Dunkle, about 15 percent of students who seek treatment at CAPS are referred to outside treatment after one or two sessions there. This was the case for Emily, who was encouraged to seek off-campus treatment because of the weeks-long waitlist.

There are many situations when it makes perfect sense for counselors at CAPS to refer a student to outside treatment – oftentimes, a student will arrive at CAPS with acute needs that require a dedicated care team, or complicated needs that require uninterrupted long-term therapy and psychiatry.

Weinberg junior Tasha Petrik was referred out of CAPS after her first appointment in October of 2017, and found the services she accessed through the referral to be a good fit. But the process of getting to that first appointment with her outside therapist was long and arduous, during a period of time when her mental health was already at a low point.

“It kind of felt like I was going through steps to prove how bad I was ... like, ‘do you really need therapy,’” Petrik says. “No one said that to me, that wasn’t their goal, but having to jump through so many hoops to go somewhere ... it made me feel like I had to keep justifying that I was bad enough off to get therapy.”

After Petrik reached out to CAPS via their online sign-up form, she was asked to schedule a 15-minute intake phone consultation with a CAPS counselor, but because Petrik’s class schedule conflicted with most of the available times, it took about a week for her to actually have that phone call.

“I don’t know what the point of [the phone call] was, frankly,” Petrik says. “There’s really not that much you can talk about with someone over the phone in 15 minutes with someone that you don’t know, they’re basically like, ‘Do you have typical signs of depression?’ and I was like, ‘Yeah, that’s why I’m calling.’”

After that phone call, it took another week for Petrik to get an in-person intake appointment due to the lack of available times outside of her class schedule. After that, she spent two weeks working through CAPS’ referral list to find an outside therapist who practiced nearby. All in all, it took a month from when Petrik first reached out to CAPS for her to meet with her therapist – a month that, Petrik says, could have been much shorter if CAPS had more availability and cut down on steps like the 15-minute phone call consultation.

Weinberg senior Callie Leone was seen at CAPS for 12 sessions during her sophomore year, before the elimination of the 12-session limit. At the end of her final session, Leone was referred to outside therapy and psychiatry practices – only to find that, like Emily, and like many other students at Northwestern, her healthcare coverage would leave her with weekly copays in excess of $100.

“[The counselor] said, ‘the good news is, now you know how your insurance works, the bad news is ... it doesn’t work.’ She was super up front with me about it,” Leone says. “She was like, ‘it’s going to be super tough for you, because ... unless you’re going to spend $6,000 dollars this year [out of the deductible], everything is coming out of pocket.’”

But Dunkel says that CAPS works hard to ensure that students find affordable outside options.

“My staff, especially Meghan [Finn, CAPS’ Care and Referral Coordinator] is really good at navigating insurance plans,” Dunkle says. “Sometimes it’s really tricky, but we will help [students] try to find someone in the area who is on their plan and affordable. We will even go so far as if in the past, if a student can’t afford a co-payment, if we can find financial resources for them, we do – we spend a lot of time on that. We also just got another gift recently for that exact purpose, to help with copayments and things like that, because I didn’t want finances to be a barrier, and neither does my staff.”

Leone, however, had never been informed of this option – neither had Petrik, Emily or any of the other students talked to for whom cost had prevent from accessing the providers they’d been referred to by CAPS.

For many students, the high cost of copays for those with insurance or out-of-pocket expenses for those without it can present an insurmountable barrier to seeking mental health treatment. But there are other reasons that a student whom CAPS has referred to outside treatment may be unable to actually access treatment. For some, “cultural taboo can make it difficult for students on their parents’ health insurance to explain what they need treatment for.”

Yet Leone feels that the structure of her visits with CAPS didn’t sufficiently equip her for the transition to outside care, leaving her feeling abandoned at the end of her last session.

“The problem was, I would see the psychologist, and we would have these kind of meandering discussions,” Leone says. “Which is fine if you can see someone for a period of several months, or if you’re time-indifferent, but if you only have 12 sessions, you need a super structured program. Because I feel very much like I got dropped off at the end of it, like I was keeping count of sessions, but I was trying to think, like, ‘is this my 11th or 12th?’ And then it’s like, ‘Okay, we’re done today! Goodbye!’”

Underfunded, Understaffed

Because Northwestern does not publish or disclose budget information, there is no way to know what CAPS’ annual operating budget may be. In October of 2016, University President Morton Schapiro told the Daily that there is “no financial limit” to CAPS’ funding, saying, “We’ve given CAPS everything they’ve ever asked for and will continue to do (so).”

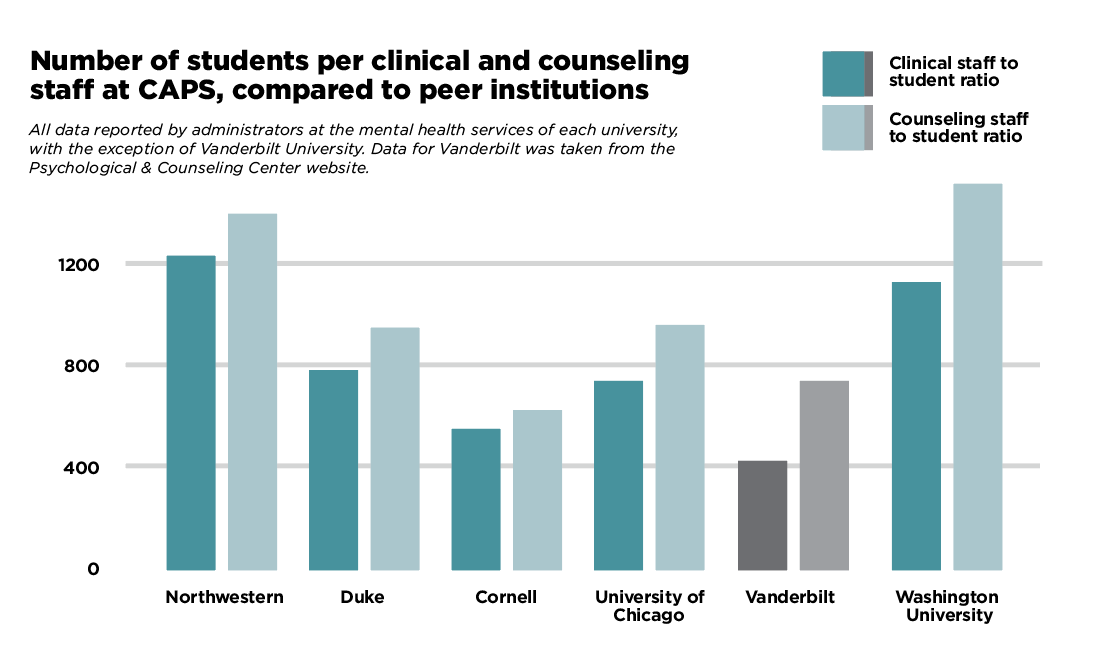

What we can analyze, even without access to CAPS’ budget information, is the number of clinical staff members at CAPS. According to Dunkle, CAPS employs 13.7 full- time equivalent clinical staff on the Evanston campus - 14 individual staff members in total, one of whom works part-time. Dunkle says that the clinical staff at an institution like CAPS fall into two categories – first, psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses and residents, who primarily handle medication management, and second, psychologists, counselors, social workers and psychology post-docs, who primarily handle individual and group counseling sessions. With a total of 16,675 students on Northwestern’s Evanston campus, this means there is one clinical staff member at CAPS for every 1,217 students, and more specifically, one counseling staff member for every 1389.6 students.