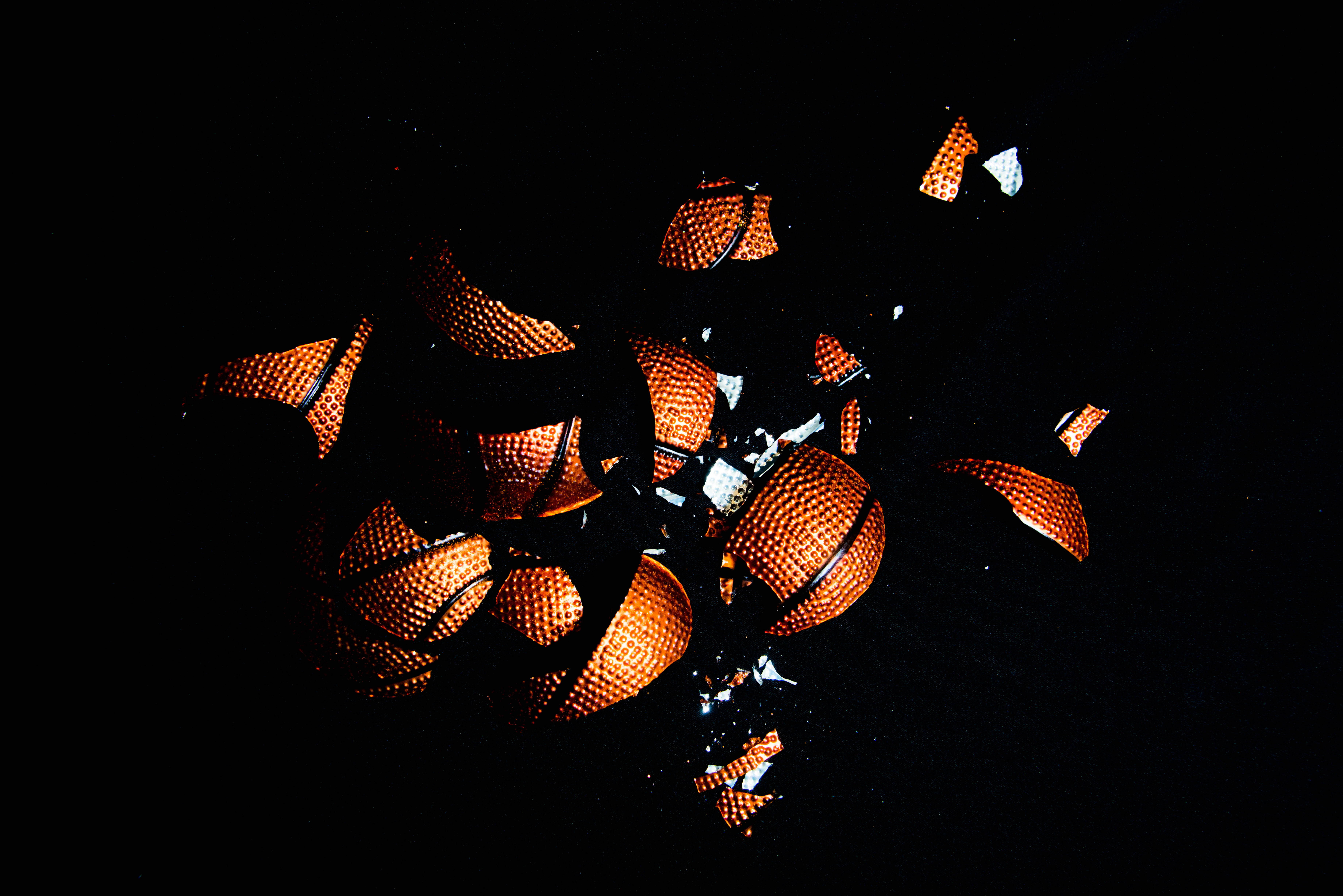

Boxed out

Even at the most supportive schools, NCAA policies can make athletes feel powerless.

By Will Fischer

- Top

- A rigid structure

- The NCAA's complete control

- Vassar’s version

- Northwestern within a problematic system

Twelve months ago, Weinberg sophomore Paulina Anasis stopped playing softball. For most of her life, the sport had been her central passion, one of the places she felt most comfortable. But now she prefers to not even think about it. Her parents don’t bring it up – it just causes too much pain.

In September 2015, Anasis arrived at Northwestern as one of only a few freshmen on a full athletic scholarship for softball. She’d waited for the day since 2013, when she committed to play softball at Northwestern as a high school sophomore. Anasis says she chose NU over superior softball programs because she wanted a challenging academic environment and a passionate coach, which she found in Northwestern softball head coach Kate Drohan. “When I came for my visit here, [Drohan] basically told me and my parents that the difference between us and other schools is that I will take care of you like you’re my own child,” Anasis says. “So I looked up to her and always just wanted her approval and to impress her.”

Drohan’s players have described her as “intense” and “really tough.” In April 2014, The Daily Northwestern published a profile on Drohan’s “success through tough-love leadership,” writing that most of her recruits initially feel intimidated and that at one tournament Drohan heckled a recruit through the center-field fence.

Drohan, who became head coach in 2002, aims to get the most out of her players, making them stronger women through a regimented team culture – and Anasis says she was looking forward to it.

“I’ve been playing softball a particular way my whole life, and a lot of the reason I got recruited was because I have a lot of personality when I play. I’m very upbeat and fun,” Anasis says. “Kate is a very focused person, and I admired that about her. I wanted her to make me better and stronger, and more focused and hard-headed.”

Anasis was dedicated to softball, but understood there was more to life than the sport. In high school she penned a blog post on balancing softball and life, writing, “I hope that my fellow student-athletes can find the balance between their commitment to what they do and their commitment to who they are because it is a muffled reflection of what they will one day turn out to be.”

“She’s 100 percent herself in every way,” says Aubrie May (Comm ‘16), Anasis’ former teammate on a high school travel team and at Northwestern. “It’s a beautiful thing. So many people worry about what others think and she doesn’t.”

While Anasis wanted to please her coach, she didn’t want to fundamentally change the way she had always lived and played the game she loved. But her personality clashed almost immediately with Drohan’s philosophy. Anasis barely played, pinch hitting only three times, even in early season tournaments, when coaches typically rotate their squads the most. As her teammates competed for playing time, Anasis felt like she wasn’t getting a chance, and says she became increasingly isolated and alienated. But her options were limited.

“Essentially, they are giving me a lot of money to carry out a job, and it’s kind of like if your boss doesn’t like the way you do that, you can’t just quit your job,” Anasis says. “You have to re-think how to do that [ job], especially if you have a contract for four years. I would describe that situation as trapping … You have to change, but it’s also like, how much can I change myself for my job?”

Drohan and a current softball player declined to comment for this story, citing privacy laws.

- Top

- A rigid structure

- The NCAA's complete control

- Vassar’s version

- Northwestern within a problematic system

A rigid structure

The NCAA might not agree with the exact language Anasis uses, but the business-like contractual agreement between student-athletes and their respective schools definitely exists. The NCAA and schools like Northwestern pay for all the expenses of a college education – tuition, fees, room, board and books – and most schools, including Northwestern, also offer other types of support, like academic advising services and priority class registration.

In return, student-athletes must “conduct themselves in an appropriate manner at all times,” according to the NU Athletics Student- Athlete Handbook. That includes passing their classes, following the rules and being a generally upstanding member of their team. The handbook tells Northwestern athletes to follow the P.R.I.D.E. policy, which stands for Perseverance, Responsibility, Integrity, Dedication and Education, a values statement intended to “guide the actions of the members of the athletic community.

The end goal for the NCAA and its member schools is to generate revenue and improve their reputations through sponsorships, television deals, merchandise, tickets and alumni donations. Though they’re technically non-profit entities, they compete intensely to build the best facilities, attract the best players and win the most games – all of which costs money. In fact, Northwestern has invested over $400 million in athletic facility projects in attempt to vault itself into an “elite area,” says Jim Phillips, NU’s Vice President of Athletics and Recreation.

“I don’t know many programs in the elite area that don’t have [these facilities],” Phillips says. “It’s an investment in a program that’s really important to us.”

The contractual agreement student-athletes enter seems like a great deal for all sides – until something goes wrong. If a player violates a team or NCAA rule, they could lose their scholarship. But what if, like in Anasis’ case, the coach and player don’t get along, and the player suffers?

The only real option is to transfer, which is often an exceedingly difficult and complicated process. But Anasis didn’t want to transfer – she loved Northwestern. She came for the academics and, outside of softball, she’d found a home on campus. So she kept pushing and working harder, trying to earn playing time and carve out her place on the team. But it never happened

In March 2016, Northwestern suspended Anasis indefinitely from the team for a conduct violation. A spokesperson for NU Athletics declined to comment, citing privacy laws. By that time she was calling her parents, crying, on most trips to away games. Anasis left Northwestern for Spring Quarter 2016, describing herself as “severely depressed and severely anxious.”

With time away from the team, Anasis healed. She moved out of Bobb and lived near her treatment center in downtown Chicago. After a few months, she went back home to Santa Ana, California, where she received more treatment and got a summer job at a local family-owned restaurant. Since her separation from NU Athletics, Anasis says she’s had almost no mental health issues, and she’s since returned to Northwestern as a full-time student.

Northwestern granted Anasis a medical non-counter for mental health reasons before her sophomore year began, a type of financial aid category usually used for a student-athlete who has suffered a career-ending physical injury, but still has an expectation to receive rightful academic aid. It’s like an insurance policy for student-athletes – if they can no longer provide athletic services as part of their contract with the NCAA, their education isn’t at risk. Anasis feels lucky to still be a student at Northwestern, but in the last year, she says she’s lost a large part of herself.

“My parents know not to talk to me about it because I like to think about that part of my life positively,” Anasis says. “To reflect on last year would tarnish softball as something in my life.”

- Top

- A rigid structure

- The NCAA's complete control

- Vassar’s version

- Northwestern within a problematic system

The NCAA's complete control

Anasis’ experience isn’t entirely unique – many student-athletes don’t get along with their coaches. Sometimes it becomes a problem and sometimes it doesn’t, but all too often, the student-athlete is the one who suffers. This is largely due to the power structure of the NCAA: The organization and its member institutions make all the rules and regulations, and if athletes want to play, they must comply. On a day-to-day basis, it’s seen most clearly through player-coach interactions

“I think it’s obvious that the coaches have a great amount of power over the players,” says Kain Colter (WCAS ‘14), a former quarterback on the Northwestern football team. “Everybody wants to play on Saturdays, and they don’t want anything to affect that. The coaches obviously have control over who’s going to play and really, kind of the guy’s status on the team, so I think going against anything the coaches are opposed to can put that in jeopardy.”

Colter has been battling the NCAA since January 2014, when he attempted to unionize the Northwestern football team and formed the College Athletes Players Association (CAPA). Colter says the NCAA’s economic motivations, along with a lopsided power structure, aren’t difficult to establish.

“All you have to do is look at these huge endorsement deals that these sporting apparel companies are giving to these universities,” Colter says. “Look at the coaches’ salaries, look at the amazing facilities being built, all of this is revenue generated off the backs of the players, and there’s nothing amateur about it.”

This “facade of amateurism,” Colter says, denies college athletes equal protection under the law. The NCAA and its schools maintain that college athletes are students – not employees – and don’t have all the same rights employees do, such as collective bargaining. In fact, Walter Byers, the first executive director of the NCAA from 1951-88, admitted to creating the term “student-athlete” in 1964 to avoid paying workers compensation.

“[The] threat was the dreaded notion that NCAA athletes could be identified as employees by state industrial commissions and the courts,” Byers wrote in his 1995 book, Unsportsmanlike Conduct: Exploiting College Athletes. “We crafted the term student-athlete, and soon it was embedded in all NCAA rules and interpretations as a mandated substitute for such words as players and athletes.”

Amid mounting pressure and countless legal battles, the NCAA and its member schools have improved conditions for their student-athletes over time, offering increased medical coverage, removing various scholarship limitations and paying court settlements to players who were previously wronged. But neither the NCAA, nor any NCAA school, has ever conceded that student-athletes are employees, or that they should be treated as such.

In March 2014, National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) Regional Director Peter Sung Ohr went against the NCAA, ruling the NU football players were employees because they dedicated more time to football than their schoolwork, and more time than most full-time employees do at their jobs. It was a monumental decision, challenging the fundamental nature of the NCAA.

Chaos ensued. Coaches, administrators and universities across the country, including NU head football coach Pat Fitzgerald and Northwestern, took a hard stance against unionization, doubting its necessity and questioning the ramifications. The decision threatened to disrupt the status quo and upend the power structure the NCAA had enjoyed for decades.

In August 2015, after Northwestern appealed Ohr’s ruling, the five members of the NLRB in Washington unanimously agreed to not exert jurisdiction, fearing a decision would harm labor stability. The status quo remained intact. But at the same time, the NCAA’s power structure was affecting another Northwestern athlete.

- Top

- A rigid structure

- The NCAA's complete control

- Vassar’s version

- Northwestern within a problematic system

Vassar's version

Communication junior Johnnie Vassar played his first minutes for Northwestern on Nov. 22, 2014, scoring two points in a 68-67 overtime win over Elon. Vassar scored only 13 more points the entire season, playing sparingly in 18 games. On March 30, 2015, 18 days after the final game of the season, Northwestern announced Vassar was transferring, and Vassar tweeted a statement confirming his decision.

But Vassar never transferred. He was no longer a member of the basketball team, but he was still at Northwestern. For over seven months, no one on the outside really knew what had happened.

Things became clearer on Nov. 14, 2016, when Vassar filed a lawsuit against Northwestern and the NCAA. The suit claimed that NU head coach Chris Collins and his coaching staff harassed Vassar to transfer, forcing him off the team and making him perform “janitorial and maintenance duties” for the athletic department. By May 5, 2016, according to the lawsuit, the university replaced his athletic scholarship with a full academic scholarship. Northwestern responded in court on Jan. 31, 2017, arguing Vassar wanted to transfer and willingly signed a “Non-Participant Scholarship Status” agreement, removing himself from the team and working an eight hour per week service requirement in the athletic department to maintain his athletic scholarship.

Both Vassar and Northwestern declined to comment while the lawsuit is still pending.

Regardless of how things actually played out behind the scenes, the story is the same – a coach and a player didn’t see eye-to-eye, and the player suffered. In the lawsuit, Vassar claims Collins “berated” him after a game in February, telling him he “sucked” at basketball, “had a bad attitude” and “didn’t do ‘shit’” when he was in the game. The quick, bouncy Vassar seemed to fit well enough on Collins’ upstart team in his second year at the helm. But according to Vassar, it didn’t work out that way.

Vassar tried to transfer, reaching out to schools like DePaul, Utah and Georgia Tech. But according to his lawsuit, none of the schools wanted him because he’d have to miss an entire season due to the NCAA’s year-in-residence bylaw. In the NCAA’s dense 37-page Transfer Guide (its stated purpose is to help understand transfer rules, but good luck), it says transfers must spend one academic year in residence at their new schools before they can compete. Basically, they have to sit out a year before they can play.

The rule intends to prioritize education over athletics, but it can harm student-athletes. The NCAA also has something called a five-year clock, meaning student-athletes only have five years of eligibility from their initial enrollment. Not only does the year-in-residence take up one of those years, but it also discourages schools from acquiring the older transfers. The NCAA caps its Division I men’s basketball scholarships at 13 per team; many schools would rather invest in a younger recruit with more years of eligibility.

Vassar’s case is part of a national class action lawsuit brought against the NCAA by Hagens Berman, a Seattle-based class action litigation law firm. Steve Berman, the Hagens Berman attorney representing Vassar, is challenging the legality of the year-in-residence bylaw, arguing the rule is a violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act. Passed by Congress in 1890, the Sherman Act prohibits companies from attempting to control a market, with the goal of promoting fair competition. By regulating the free movement of players, Berman’s argument is that the NCAA is restricting competition, preventing the best matching of players and schools. Over the past three years, Berman has won at least $248 million in settlements for college athletes through alleged NCAA antitrust violations, from video game licensing to scholarship caps.

- Top

- A rigid structure

- The NCAA's complete control

- Vassar’s version

- Northwestern within a problematic system

Northwestern within a problematic system

Northwestern Professor Robert Gundlach has seen this pressure build on many of the NCAA’s policies, and he himself has worked to improve the student-athlete experience. Gundlach, a linguistics professor and the director of the Cook Family Writing Program since 1977, has served as Northwestern’s faculty athletics representative to the NCAA and Big Ten since 2002.

Gundlach’s main priority is promoting the ‘student’ in student-athlete. A disciplined believer in the value of a college education, Gundlach believes NCAA athletes should receive the best academic experience possible. Accordingly, Northwestern does this better than almost every other school in the NCAA, scoring a 97 percent overall Graduation Success Rate in 2016. It’s a source of pride for NU, so much so that Gundlach served as interim athletic director for three months in 2008. At other schools, the commitment to education isn’t as evident – in 2014, an athletics report at the University of North Carolina found that the school engaged in 18 years of academic fraud largely to keep its athletes eligible – meanwhile, Northwestern put a linguistics professor in charge of its athletic department.

In addition, Colter called Northwestern a “pioneer” in offering protections for its student-athletes, as it was one of the first schools to offer multiyear scholarships and grant aid up to the full cost of attendance. So why, at one of the NCAA’s model institutions, have there been claims of mistreatment, lawsuits and a call to unionize?

According to Colter, it has a lot to do with the NCAA’s fundamentally broken system. But Northwestern still has room to improve, he says, and that’s why student-athletes need representation. Colter says he and the NU football players didn’t organize because they felt Northwestern was specifically mistreating them, they did it to improve the rights of college athletes across the NCAA and gain equal protection they felt entitled to under labor laws.

Anasis also believes these issues stretch far beyond Northwestern. In order to compete, NU must work within the NCAA’s rules and regulations. That includes convincing young high schoolers to verbally commit to entering contractual agreements. After beating Indiana in January, Communication junior and NU point guard Bryant McIntosh casually called this recruiting process “a business” without any response from the press room. But at such young ages, Anasis says coaches have no idea how a recruit’s personality or athletic ability will develop, and as part of the business, the athlete can become the neglected worker.

In the NCAA’s existing power structure, student-athletes at Northwestern and all over the country are limited under their contractual agreements. When something goes wrong, whether it’s a disagreement between player and coach or an unexpected development in a player’s life, Anasis says these student-athletes can all experience a similar feeling, one that is constantly perpetuated by the NCAA: “trapped.”